Mothers. They, as part of the parental power couple, are the villains in everything from psychoanalysis to career choices and marital partners. And while there may be many unjustly accused, all prejudices germinate from the same seed of truth – that all of us grow in the direction of our sun – and either flourish or wither beneath its gaze… Mothers can make us or break us.

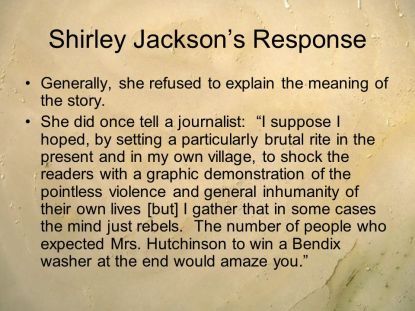

“The first book is the book you have to write to get back at your parents… Once you get that out of your way, you can start writing books.” Shirley Jackson (Franklin 30)

For those of us who write, there is perhaps no truer statement – especially if our youth was riddled by the constant misfire of incompatibility, of conflicting dreams and expectations for ourselves. But this is a good news/bad news proposition: it is bad news if the emotional worm bores into our souls and cripples our ability to write what needs to be written; it is good news if we can learn to tap into the honesty of the subsequently generated emotions and – through our writing – (instead of degenerating into psychic messes) work competently through the layers of universal truths.

It has been done before. And one of the best examples is that of Shirley Jackson, whose own relationship with her mother sadly tainted both her self-image and her self-confidence, but led to some totally awesome Literary Horror.

History and the Other Inconvenient Truths

Of all the women writers of American Horror, Shirley Jackson is queen. She set the stage and the bar for the writing of modern Literary Horror, influencing generations of writers in ways we never suspected, leaving us examples that are more easily digested when Critics attempt to explain how they look at our genre. While a lot of what she wrote might today be considered Young Adult fiction and is still taught at the high school level, the subject matter is pure adult – tapping into psycho-social behaviors that still shock and disturb, yet also resonate with our adult memories of our younger selves.

She didn’t set out to write Horror – her influences were typically Literary ones, her husband a Literary Critic. But her work held the roots of Horror in its curled fingers – and all because of her complicated relationship with her mother.

Horror has long been the Literary vehicle for expressing the conditions and humanity of the oppressed. It’s something women commandeered in their writing during the late 1800’s, following along the path that writers like Charles Dickens and Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters had blazed. And like it or not, it was because of the second-class status of women and minorities that provided the impetus. When one group of people (then as often now largely legally and politically empowered white men) have absolute command over “Others” – be they women or immigrants or minorities – in which lives are lived subject to incarceration, psychiatric experimentation, homelessness, poverty, untreated illness, wretched working conditions, physical and or verbal abuse – terror is the result. Post-Traumatic Stress is the result. Mental illness is the result. Violent pushback is the result.

Women writers were often the privileged prisoner-witnesses when not victim to these events, bearing testimony from their own strata of society, often identifying with those they witnessed being mistreated when not suffering their own class-tinted versions. Sometimes these women were so moved that they attempted to represent the classes they saw suffering – such as Harriet Beecher Stowe with Uncle Tom’s Cabin (https://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/SAYLOR-ENGL405-7.3-UNCLETOM.pdf ) – the first successful attempt to bring due attention to the inhumanity of slavery, Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2802 ) – highlighting the brutal consequences of mixed race life in Mexican Colonial California, or Ann Sophia Stephens’ Malaeska: the Indian Wife of the White Hunter (http://www.ulib.niu.edu/badndp/dn01.html )– one of the first attempts to bring the plight of eastern Native Americans to light.

Of course these stories were meant for other women’s eyes, written in overly sentimental and “emotional” tones that decried them women’s reading material instead of Literature, and they were at times every bit as ignorant and romanticized as “imagining” how others live can be. But they were also meant to unite and more importantly, to enlighten and then incite. Literature they became. And being embraced by generations, they also became transformative works that changed many early American minds about the plight of all “second-class” citizens.

Jackson serves this purpose in American Horror. In Jackson’s case, her stories reveal the “normal” lives of women of her generation (1916-1965) – a time and place close enough to our own that we seldom remember the constriction of society against women and girls even then. We tend to gloss it over, to misremember it with Donna Reed-like complacency. Says Jackson biographer Ruth Franklin:

“…tension animates all of Jackson’s writing. And it makes her perfectly representative of her time…The themes of Jackson’s work were so central to the preoccupations of American women during the postwar period that Plath biographer Linda Wagner-Martin has called the 1950’s ‘the decade of Jackson.’ Her body of work constitutes nothing less that the secret history of the American women of her era. And the stories she tells form a powerful counternarrative to the ‘feminine mystique’ revealing the unhappiness and instability beneath the housewife’s sleek veneer of competence.” (Franklin 5-6)

I remember the cracks that showed in the early sixties when I was a child, my own mother born in the 1930’s, discussing things across the backyard fence with other wives, the way in which there was still a tiptoeing around the man of the house, routine sacrifices demanded of wives for their husband’s public face and personal careers, the arguments and lectures about compromising the “appearance” of things, the dispensing with a mother’s complete life and career because the new one was the children she was expected to have for the good of the husband’s career advancement. My own mother did not learn to drive until her thirties… a demand she made after she suffered a miscarriage while unable to get herself to the base hospital in time.

We could argue that it is natural for people to forget the discomfort and unpleasantries we have survived – whether as a group, a gender, or an individual; so it is that today we tend to have conveniently forgotten what recent generations of women have endured, preferring to remind ourselves that once upon a time, things were much, much worse for our gender. It is as though distance makes it easier to look at. And it makes us wont to repress any criticisms of where we are now, lest we seem ungrateful for the advances we have achieved…or worse, rabble-rousing and unfeminine.

When we consider writing as a reflection of our own times – of writing modern Horror and revealing the truths of today’s social issues, we go wooden. We recognize that it is that very oppression which makes us decide whether we want to “come across” as militant and angry women, or “reasonable” and “compassionate” as we are taught to believe “normal” women are. It scares us as women and as writers back into complacency. Worse, it puts phantom voices in our heads, whispering what some people might think of us if we really said that…

We think about how our parents will respond, what our own mothers will think of us. We remain unsure of the consequences if we tell our secrets. We let this affect storylines and word choice, character development and how we evolve them. We think we can tell stories with half-truths and are surprised when editors say they are lackluster. We begin to belittle the very things that eat at our souls and take so long to work their way out of our bodies like splinters — sometimes leaving Literature in their wake, sometimes leaving orchards of trees bearing too little or shriveled fruit. We hear the criticisms of society and our parents… and we let them silence or mutilate our voices.

We may be survivors of something, but we don’t want to be called warriors…we don’t want to draw hurtful criticism, or worse – enemy fire – especially from our own intimate camp. We women, it seems, can be our own worst enemies…

There is even now a separation between protesting our circumstances as righteous anger, and behaving in a socially acceptable manner; today as before our patriotism might be challenged or our sexual preferences. It’s driven many a writer to Literature and genre fiction… Because it is there that the awful truth of damage and ruin can be revealed with less criticism, hidden in plain sight because it is a societal normal. It is there that any oppressors can “overlook” the rebellion, not seeing it in fiction because they don’t see it in real life where it is also hidden in subtext – coded as the way things are, or because they can belittle it as “women’s writing” as… pulp… inferior, toothless ranting.

But particularly in its preservation, an analysis of Literature in retrospective remains also the fact that we do see it – the oppression of times, the flaws of relationships, the vulnerabilities of self.

The work of Shirley Jackson is as much a loud confession and a work of rebellion as it is a recognized body of Literature – Horror Literature.

From her poisonous relationship with her mother, her constant reconciliation with the fact of a constantly unfaithful husband who she loved passionately and her mother opposed, the minimizing of her writing by everyone including herself, the professional ostracism of the Academic community, the struggle to raise children in the midst of so much and so constant criticism – it all led to private battles with her own self-worth and subsequent brushes with mental illness…all of which color her fiction with immaculately concealed screams.

Because of its honesty, the work becomes elevated.

Says Horror Critic S.T. Joshi of Jackson: “…I wish to place Jackson within the realm of weird fiction not only for the nebulous reason that the whole of her work has a pervasive atmosphere of the odd about it, but, more importantly, because her entire work is unified to such a degree that distinctions about genre and classification become arbitrary and meaningless. Like Arthur Machen, Shirley Jackson developed a view of the world that informed all her writing, whether supernatural or not; but that world view is more akin to the cheerless and nihilistic misanthropy of Bierce than to Machen’s harried antimaterialism. It is because Shirley Jackson so keenly detected horror in the everyday world, and wrote of it with rapier-sharp prose, that she ranks as a twentieth-century Bierce.” (Joshi 13)

This is high praise indeed, and praise overdue. But it is also a call to arms for women writers of Horror…horror in the everyday world….Do you not know horrors that like Stepford Wives we pretend not to notice lest they notice us? These are Literary links…world shakers….Inconvenient truths.

States biographer Ruth Franklin: “Critics have tended to underestimate Jackson’s work: both because of its central interest in women’s lives and because some of it is written in genres regarded as either ‘faintly disreputable’ (in the words of one scholar) or simple uncategorizable. Hill House is often dismissed as an especially well written ghost story, Castle as a whodunit. The headline of Jackson’s New York Times obituary identified her as ‘Author of Horror Classic” – that is, “The Lottery.” But such lazy pigeonholing does an injustice to the masterly way in which Jackson used the classic tropes of suspense to plumb the depths of the human condition.” (Franklin 6-7)

“Dismissed” and “overlooked” is indeed the best way to describe Jackson’s body of work in its own time. Like other “greats” before her, her subjects found their way under her readers’ skins and held out to Critics an ornamentation of honesty so many of us are not comfortable with when expressed in plain English – the adolescent awakening of honesty, of not-liking one’s own parents and the societal implications of being not-liked back. It did not help that like many women who feel made powerless, she publicly embraced witchcraft – describing herself as a “practicing witch” although exhibiting more of an intellectual interest than that of more serious dabbling in the occult. (Lethem vii-viii)

This could only serve to push Critics further away from her, raising the ire of a more conservative public who cancelled subscriptions and declared themselves incompatible with such disturbing writing as found in “The Lottery,” denouncing it as “nauseating” “perverted” and “vicious”… (Lethem viii)

Yet she and her fans endured. It was, perhaps, because Literature has a way of seeking out the subtext – of stripping away the witchcraft of character and plot and seeing world view – the truths of historic period revealed by the people who live them. This leads to a dedicated fan base – one that simply does not go away and signals to the Critic that there is something more in the writing. But this seldom happens during the writer’s lifetime…

Jonathan Lethem explains in his introduction to We Have Always Lived in the Castle (New York: Penguin, 2006, c1962): “Jackson is one of American fiction’s impossible presences, too material to be called a phantom in literature’s house, too in-print to be ‘rediscovered,’ yet hidden in plain sight. She’s both perpetually underrated and persistently mischaracterized as a writer of upscale horror, when in truth a slim minority of her works had any element of the supernatural…While celebrated by reviewers throughout her career, she wasn’t welcomed into any canon or school; she’s been no major critic’s fetish…” (xii)

And according to Franklin, even Jackson’s husband was distressed and perplexed at the professional ostracism:

“[Stanley Edgar] Hyman[an important intellectual and author of several major works of literary criticism] was a consistently insightful interpreter of his wife’s work. He bitterly regretted the critical neglect and misreading she suffered through her lifetime.” (Franklin 9) According to her husband, “she received no awards or prizes, grants or fellowships; her name was often omitted from lists on which it clearly belonged…” (9)

Yet her impact is undeniable – palpable, connecting to women and young women even today. Like many of her gender, Jackson’s writing has been left adrift – largely as consequence of an inability to reconcile real issues within the rigid interpretations of a Literature still evolving its theories and conjecture on how writing happens. But the public noticed – her public, often filled with young women who could identify… Because her writing captured the most important of Literary elements – resonance with generations of readers.

Indeed, we all have mothers who criticize to guide, we all have various infidelities that interrupt and scar our lives, children who complicate our decisions, Professional ceilings to crack our heads against when they do not collapse outright upon us. Jackson’s audience knows her vulnerabilities and feels her angst and subversive anger.

Joshi continues that the importance of her domestic fiction (which he describes as domestic horror) lies in the fact that Jackson “systematically attempts to present what may in reality have been highly traumatic events as the sources of harmless jests…it rests in its employment of very basic familial or personal scenarios that she would reuse in her weird stories in perverted and twisted ways; things like riding a bus, employing a maid, taking children shopping, going on vacation, putting up guests, and, in general, adhering – or seeming to adhere – to the ‘proper conduct’ expected of her as a middle-class housewife.” (Joshi 17).

Jackson’s fiction survives because not only is it truthful, but we can still see the truths as being in our lives today in various degrees. And, we are glad somebody has the brass to speak it.

Mommy Dearest

So with all of these social battles, why is it that it is the one we have with our mothers that tops them all?

Perhaps because our relationship as women is most intimate with our mothers; here, all pretense is stripped away. They know our secrets. They know precisely our vulnerabilities. They know how to hurt us and have immediate access to do so. All of our future ability to trust others is attached to our parents – but most deeply to our mothers… So much so that they can scar us permanently, whether they are even present at all.

Mothers can’t win. But if they are or choose to be their daughter’s worst enemy, the damage is devastatingly deep. Where bad maternal and absent maternal relationships with daughters have been the subjects utilized in many great Literary plots, few have gone where Shirley Jackson went.

Classic Literature had long been where domestic abuse and the manipulation of inheritance laws became the source of many a ghost story, with mad women in attics, and the ghosts of dead babies and drowned young women facing pregnancy and ruined reputations littering the mythology of many a fine family, each generation – each era – having its own denigrations and disappointments, its own secrets. In that Classic venue most of the resentments and tragedies were handled by heroines who were vulnerable and ultimately, unfailingly “good.” Evil stepmothers, greedy mothers, absent mothers… it was the daughter who through her own inherent goodness would triumph at last.

So everything that came before set the stage for a shift in truth: that sometimes such mothering does not produce “goodness” but savagery.

The final spotlight wrought by Shirley Jackson came to shine upon the biggest resentments of all – the resentment of daughters against mothers who fail to protect them in their own attempts to protect themselves and their mutual reputations, and the resentment of mothers against daughters who impulsively disregard their hard-won advice or blatantly sabotage the best laid plans. Jackson’s writings seem to drag us into the world where best intentions and robotic obeisance lead to isolation and the celebrated road to Hell.

It was honest. Painfully so. And every parent and child has been there to some degree. We live our lives in constant push-back, testing the boundaries of our respective worlds, craving acceptance and praise, risking it all on impulse and frustration. We tend to live our lives specifically to spite each other.

So when we are not blessed with that Carrie Fisher/Debbie Reynolds mother/daughter power relationship, the rough edges wound and eviscerate instead of nurture and heal.

Many a woman has grown up feeling that she was quite accidental, if not being told so. She becomes a burden, an inconvenience that constantly threatens the happiness of her family. She is a point from which it all potentially comes unglued and reputations can be slighted, she is all of the dreaded and unsightly mistakes of her parents. The pressure to get it right is often overwhelming.

Even when we say we don’t care, we do. After all, if our own parents don’t love us unconditionally, what possible life can we have in a world full of cruelties and misadventure?

It took Shirley Jackson to open that door. And she went as far as matricide in her writing. Imagine that in a Classic Literary heroine…

Says biographer Ruth Franklin in her new book, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life:

“This does not mean that Jackson actually wished to kill her mother any more than the frequent appearance of sexual molestation in her fiction means that she was literally molested. But it is clear that even from California, [her mother] Geraldine managed to insert herself into her daughter’s life in a way that Jackson resented, criticizing her appearance and offering unsolicited advice on household help, clothing, furniture, and other domestic matters.” (Franklin 350)

It simply means that the relationship between mothers and daughters is every bit as potent and potentially toxic as that often attributed to fathers and sons… Women are simply more societally pressured to suppress our rebellions.

And sometimes that suppression, the reluctance to consciously acknowledge the personal evisceration, leads to great Horror.

Franklin continues: “On one level, the ‘explosive’ material clearly touched on her own feelings about her mother. All of Jackson’s heroines are essentially motherless, or at least victims of mothers who are not good enough…” And the character – Elizabeth – “ would be the first of Jackson’s characters to commit matricide; the act also takes place in her last two completed novels…”(350)

As writers, sometimes our characters have to say what we mean, to do symbolically what can’t be done in real life.

Still, the constant bullying by her own mother took its toll, both in Jackson’s mental health and in determining the direction of her fiction. And sadly, many writers know all too well this type of unsettling relationship with kin.

Continues Franklin,“Her [mother’s] letters to Jackson are masterpieces of passive-aggression, disguising harsh critiques beneath a veneer of sweetness. She needled Jackson constantly about her weight: ‘How about you and your extra pounds?…You will look and feel so much better without them’” (this written less than six months after her daughter’s birth), and then a year later stating in another letter in response to the successful publication of The Lottery: “‘We’re so proud of your achievements – we want to be proud of the way you look too, And really dear – you don’t do a thing to make yourself attractive.’”

Such is the relationship many of us share with our own mothers. Is it any wonder that this kind of private narrative leads to public art and writing that leans toward the Gothic, the dark, toward Horror and women’s issues? Toward Literature?

We Are All Shirley Jackson

It should come as no surprise then that during her lifetime she developed emotional struggles amid various degrees of mental illness spurred on by the stress of those fueled insecurities handed her by those she needed to trust. The result was the creation of dark-themed stories and novels with characters who could do what she could not.

In so many ways then we are all Shirley Jackson. Often we are like her: self-loathed, too tall, too awkward, and burdened with insecurities… We might be likely to assume that this was because she was at heart a writer – a creative person which is a title we stereotype into shyness and social dysfunction. But it had more to do with her upbringing, and a difficult relationship with a mother who seemed unwilling or unable to like her.

Says biographer Franklin, “As a writer and mother myself, I am struck by how contemporary Jackson’s dilemmas feel: her devotion to their children coexists uneasily with her fear of losing herself in domesticity. Several generations later, the intersection of life and work continues to be one of the points of most profound anxiety in our society – an anxiety that affects not only women but also their husbands and children.” (9)

Hers is the story of how the irritants of life and circumstance become the grit of sand upon which the pearl of Literature is made. It is a lesson in how one uses the honesty of one’s own life to shape a fiction that masks the truth of one’s times by the telling of one’s most intimate secrets. This is how Literary Horror is done – not by the overt caricature of shock and gore – but by the constant drip of the faucet everyone has and no one notices or chooses to ignore.

But the lesson is that we should never make excuses for those who have laid traps for us, never attempt to bury those hurts with substance abuse or spiraling illness and behavioral addictions. Instead we should let those wounds fester. Let the wood work its way out of our flesh, or let it lie there if it be resistant to our preferences… let it be the grit in the oyster.

Honesty and mining our most private emotions in writing is the lesson we take from Shirley Jackson. If it is big enough in our psyche to suppress our writing, to tempt us into self-destructive behaviors, to make us fearful of actually saying it, it needs to be said. And until we find a way to do so, writing will remain a struggle – clouded by emotions that block our words because left to fester unacknowledged in the dark they are cancerous.

We may have to – as Shirley said – write a lot of bad fiction to please our parents, to please who we anticipate will be judging our fiction. But in the end we have to stop caring. We have to tell the truth.

Because the truth will set you free.

References

Joshi, S.T. The Modern Weird Tale. Jefferson, NC : McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, c2001.

Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: a Rather Haunted Life. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, c 2016.

Lethem, Jonathan. Introduction. We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson. New York: Penguin, 2006, c1962.

Thank you for another excellent post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome! I have been haunted by Shirley since I first read her in seventh grade… I felt it was the least I could do!

LikeLike

Great post, very insightful. Lethem’s comment about Jackson’s work being hidden in plain sight is right on the money. Your insights about mother/daughter relationships were clarifying for me as well. All writers have hang ups (which can also be inspirations) that involve their parents. Interesting subject matter here, thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

High praise from one with piercing insights of his own! For any who don’t, I encourage a visit to oglach’s blog….the fine wine of deep thoughts and truly excellent writing await…

LikeLike

KC, this writing is excellent!!!!! I am going to tweet it out to the world so more can read it and YOU. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am going to get a big head….will need bigger avatar photo….Thank you for the compliment, and thank you for providing a voice for Native American issues. (I also seriously recommend Lara’s blog, by the way… for those who want to hear the Native perspective…accurately and at last!)

LikeLike