There are many reasons to read a great Horror novel: to scare yourself, to scare your parents, or to scare your teachers. But there is one reason that – if you write – you might not have considered: Reading great Horror novels can teach you how to write great Horror.

Seemed obvious, didn’t it?

So why doesn’t “just” reading a great Horror novel beget great writing?

The answer is: there are different ways to read fiction; you can read as the intended audience, you can read as a Critic, and you can read as a writer. And if you don’t understand the difference, you can’t put the writerly gifts hidden in Classic Horror to work.

Reading as the intended audience is easy. You pick up the book and let it take you someplace else; this is entertainment in its purest form and all control is relinquished to the author’s storytelling wiles. There is no commitment beyond the pursuit of enjoyment.

Reading as the Critic is much darker, much more motivated, colored by academic analysis: it is technical, and it is over most of our heads, requiring a great deal of preparation, such as a Classical Literature background, and an understanding of linguistics, psychology, philosophy, and history. Most of us don’t naturally go there and do not want to: it is cold, hard work that seems intent on destroying the innocent bliss of reading for fun.

On the other hand, reading as a writer is a weird marriage of the two. It is at once dependent on enjoying what you read, and then wanting to dissect it in order to understand what made you want to keep reading and what made its afterimage stay in your head. Reading as a writer is all about asking yourself how and why and when another writer managed to get it “right”… it is about studying their technique for the purpose of creating your own.

YES. READING IS TECHNICAL AND SOMETIMES ICKY

Yet for many people – writers included – it never occurs to them to read something differently.

This is in part because we don’t know how. It also doesn’t occur to us to go beyond the pondering of the magic which appears to be involved in the writing of good Horror. We tend to not want to take it apart, to look behind the curtain because it is the magic that we love to savor.

We are, at heart, a superstitious lot…

It doesn’t help that reading as a physical act quickly becomes so automatic that we are not even aware that we are performing a complex brain activity. We seem to “glimpse” a word and it magically forms images in our minds…effortlessly….mystically.

We curl up someplace snug, we open our book, and wait to be enchanted. We don’t think of reading as work, because as we grow into being readers it becomes wickedly instinctive, unconscious – even involuntary….like magic. Words take on a life of their own, threading their way through our imaginations. We begin to visualize. We become engaged in the tale. Soon, we aren’t even aware that we are reading because the story simply and spontaneously unfolds…

As writers we are looking for clues when we read.

And reading as a writer means that you will have to adapt your reading technique; you are no longer seeking entertainment alone – no longer the one being wooed. Instead, you must become a shadow Critic, poking and prodding everything from the sentence structure to characterization, from punctuation to plot, from the outside in.

To do this successfully, a couple of things must happen first:

- You must read the book for thrills

- You must understand what you are looking for

https://frankenreads.org/event/frankenstein-book-discussion/.

THRILL SEEKING ON A DARK AND STORMY NIGHT

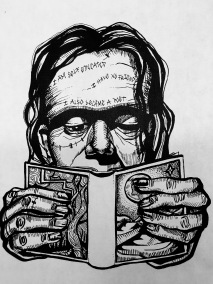

Chances are, if you write Horror, you love Horror. This means you can’t read a word of a new story or novel and not get caught up in it. Of course, that is what every author hopes for, so it is not altogether a bad thing. But it is distracting. Your imagination latches on to the prose like a face-hugging alien – pupils dilate and the pleasure centers of the brain light up like Frankenstein’s monster.

It is important, then, to read a tale first for the enjoyment – to get that habitual and natural pursuit of happiness out of the way. It does serve a purpose: you will know exactly when and where that sweet spot of being hooked and being Horrified took place.

Sometimes it even begets your own monsters, new story ideas, or creates a nice, fertile mood for drafting or brainstorming. But reading for pleasure is not reading as a writer, and it should not be mistaken for such.

Reading for pleasure is that something else: a spinning of the channels of the imagination, a hope of hooking up with a really great idea or being swept away by one.

Yet for writers of Horror fiction, sometimes even reading for pleasure can go awry because if you write Horror, you also come to wonder how it was exactly that a given story scared you… and you eventually might come to be distracted by the fact. This is especially true if you re-read the story years later, when phrases like “What was I thinking?” enter the mind because you read parts you don’t remember and you can’t find parts you thought you did read…

“What happened to the Horror?” you might ask. And exactly how did the writer cause us to manufacture details that were implied but not actually there?

This, friends and neighbors, is where Horror goes all Brain Science…

Two things are at work here:

- the writer’s technique,

- and the curious effect emotion has on human memory.

Of course, emotion is not exclusive to Horror; but Horror is – as Lovecraft so accurately pointed out – fear’s first cousin. And fear is one of the most potent emotions because of its ability to hijack the brain and create memories where none previously existed.

When we experience fear, we process it according to our own experiences, and the reconciliation of the emotion with existing memory tends to reshape the new memory as colored by the old. So when we read Horror for the first time or for enjoyment, we are surrendering our brains to the puppet-master of emotion. The monster in the dark becomes more or less sinister based on what we read and what associations we make with it.

So during our teen years, when we fear the ending of the world before we grow up and realize our lives, the monster that threatens this scenario has more scare power than the same monster will when we are at midlife or older, when we are wont to rationalize, minimalize, and offer concessions – even to monsters. While the monster lurking in the closet has more “terror cred” if the reader has ever been or imagined being attacked in their home, the threat of possession by demons more intimate if one is a lapsed Catholic with residual guilt, how much Horror is delivered to a reader totally depends on the reader’s own experiences and learned fear management.

Horror, it seems, is very personal.

So how does the writer tap into that formula that makes a specific fear generalized?

Well, we are going to have to look at technique…and it is as elusive as it is desirable. And we are going to have to admit that not all Horror will scare all people at the same time; in fact historically, much Classic Horror scared its period audiences because of how those stories related to what was happening at the time. If we are able to associate the Horror with something contemporary, the story will still scare us. This means it has to be a Horror that is bigger than the monster – the monster has to represent something bigger.

The bad news is that such success is a bit of a crap shoot.

The writer must be able to gather that perfect storm of what is most likely to scare the bulk of readers in a specific target group at a specific time and for a specific reason, the exact amount of disclosure in when, where and how to reveal the monster, and the strange magic of storytelling.

The first point means a writer must really know his or her audience and not from afar – readers will sniff out the fakers and pretenders — and to actually understand and anticipate what his or her contemporaries really fear the most in life. The second means developing a kind of sixth sense about how to pull back the curtain without shouting “ta-dah!” and flattening the curve of your climax. The third means a writer must connect to that preternatural rhythm of prose that says exactly what it needs to and no more.

And it is the second and third of those ingredients that writers can learn from doing what readers love most – reading.

But there is of course a potentially fatal flaw imbedded in every writer (reading or otherwise)…a kind of subliminal kill-switch

And the glitch is this: very few writers are Masters of Their Domain – once again, most writers are readers and read as readers first. We are addicts of prose – both our own and random words printed on pages. We can’t stop ourselves from seeking the “high” so we might as well admit it; we really do have to read a good book first as a reader. We become as dazzled and bewitched as a fairy with a Celtic knot.

Then and only then can we go back and hope resolve to read as a writer. (And if you think I am kidding, go back and read your own writing – something old that you have forgotten. You won’t fixate on the bad parts that need fixing, but you will congratulate yourself on getting the good parts handled right. Sick, isn’t it?)

We are no different with a Classic writer’s writing; we embrace and stroke the beastly prose that made us feel what we wanted. We excuse any parts we did not understand or disliked. And most of all, we let how the writer set us up slip right past us.

This is why we have to go dark. We have to use the Critic’s lens…those slime-covered glasses that dissect what we hold most sacred.

Illustration by Gustave Dore (1832 to 1883). http://wordyenglish.com/p/little_red_riding_hood.html

ALONE WITH THE CRITIC

For most of us, our only exposure to Literary Critics and analytic assessment of writing is both boring and negative. Critics are, after all (and to our knowledge), the ones who rip our favorite authors apart and insult our intelligence by stating outright that we don’t have any. They are the wolves in the sheep pen…

But what we don’t see is that the Critic means we are forever reading as readers and telling them that enjoyment means everything. Critics want more. And if you remember high school, so did your teacher. And then your professor. So why didn’t you get it? Could it be that no one ever really taught you about the many ways of reading?

The bad news is that it is perfectly possible.

For years we are asked to analyze what we read without being shown how to see words acting differently on the page…And for many of us caught in the passions of youth, we don’t want to….we aren’t emotionally ready yet.

But doing so – learning to read the same words, the same stories differently – is what helps us develop the ability to find and judge truth, to understand the use of metaphor and analogy, to separate polemic from satire. Try looking at our current internet, fake-news (which used to be called propaganda by the way), social media-led world, and NOW you see the importance of that talent…

So it was no illusion…education has always placed heavy emphasis on interpreting and deciphering prose. And all of those term papers, research papers, and required reading were about that. Yet education has never been graceful about teaching the details…because education has failed to show us the complete picture of how and why. Instead, it has served to embitter most of us about the critical process.

It made us feel stupid.

Worse, educators are great for coming up with ways to analyze writing, for some ruining the enjoyment of the Classics. And while this is a real fear for those needing to read like writers, and something that does in fact happen to some people, it does more so to those who are closet editors. If once learning how to look at language means you cannot turn it off, then you must face it: you are an academic, an editor, or a Critic. Get thee thou education and do not pass go. Be happy. Follow your obsessive bliss…because all genres need you.

However learning to approach reading academically and as a critical thinker is an important thing.

Reading as a writer is one of those irreplaceable tools every writer needs to master, and one I’d never really heard expressed as a technique before my return to the college classroom. In fact, if I had heard it in any guise before, I probably dismissed it as a cutesy way of inflating the ego. But this is a serious technique, and here’s why: especially within the United States educational system, not everyone reads enough “good” fiction or “Literature” to develop a subliminal sense of how to mimic the different elements that made those works great.

I know I have been guilty of such neglect. I always wanted to read the Classics. But for some reason, unless someone made me it didn’t seem to happen. I always felt intimidated by their greatness, I suppose, figuring that because they were such a source of study, discussion and Criticism that I would not ever fully understand them and I didn’t want to appear even more stupid.

But that is a cheap excuse. Books are books after all, written for readers. Yet I was plagued by the mystery so many modern readers are: what make a book great? What makes literature the Holy Grail of writing?

Unfortunately, it is not as mysterious and awesome as it sounds; it has more to do with the ability of a writer to accidentally or on purpose say something bigger than is stated in the story, while dazzling the reader with the competent and artistic handling of language.

This does in fact mean that some books are Literature but which are unrecognized as such – at least they are not yet. But it also means that we need to look at prose the way we’ve learned to look at poetry: it can be read for simple enjoyment, or it can be dissected and impress language technicians with double-meaning, allegory, metaphor, analogy and pure genius. The level to which you as a reader or you as a writer wish to enjoy fiction is up to you. But being willing to get down and dirty with the dissection business (something Horror writers and readers should be familiar with) can open amazing windows to understanding how great fiction is constructed.

So to learn how to write better Horror fiction, we have to do what engineers do: we have to deconstruct prose to see how the pieces came together and rendered success.

As Francine Prose (ironically surnamed as she is) states in her book Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them, you have to discover how to read analytically: to become “conscious of style, of diction, of how sentences were formed and information conveyed, how the writer structures a plot, creates characters, employs detail and dialogue” because writing “is done one word at a time, one punctuation mark at a time” (3).

One of the best ways to do this is to sit down with your favorite book or short story, and start copying it word for word. This slows you down, forcing you to notice every phrase, sentence and punctuation mark. It reveals how you were manipulated by the rhythm of the author’s own choices, why you as a reader gave emphasis to certain passages, were susceptible to others. You notice vocabulary choices, perspective, the intimacy or distance gained by wording and grammatical emphasis. These are your tools – your paints, your canvas, your textures, your lighting. This is the writer’s version of art school.

And because you are also a writer, chances are there is already a bit of the academic in you… As such, you have merely to access that natural curiosity about “memory. Symbol. Pattern. [because] These are the three items that, more than any other, separate the professorial reader from the rest of the crowd.” (Foster xxvii)

Since writing is the creation of patterns, reading is the logical reverse engineering of them.

Like art, writing is all indeed about patterns – everything from plot (of which there are various estimates as to the actual number of available “master plots” from two to twenty or more) to motifs and themes. Decoding these patterns is like deciphering a riddle the author consciously or subconsciously embedded in the text ( Prose 4-5)…

This is what close reading is all about. For example, Prose recounts and old English teacher’s assignment to read King Lear and Oedipus Rex and “Circle every reference to eyes, light, darkness and vision… Then draw some conclusion” upon which to write an essay (4). This is where Literature tends to stand out: these hidden gems lie awaiting discovery and assessment. Literature then, invites the reader back into the text multiple times, to explore potential meanings and relevances, to form opinions and make discussions.

Fiction today is really not much different. We just don’t feel as free to criticize, fearing offense or even attack by fans of the author, if not the author… Yet this is what is meant to happen to fiction. It is meant to be discussed and re-read, and even judged. That doesn’t mean that accepting criticism is easy, or that criticism is just or warranted every time. But unless you write in a vacuum, readers will find you. And they will judge, each and every one. Doesn’t it make sense that writers would write with the intent of surviving that criticism?

The fact is everyone has an opinion, for good or ill, correct or not, graciously delivered or accompanied by obnoxious and illiterate venom.

As writers, we have to detach ourselves from our own work, allowing our “children” to grow up and go out into the cold, cruel world.

We must realize that they will be judged and sometimes justifiably found wanting, but that it is ok to love them anyway.

This is the way fiction becomes Literature, the way writers test and challenge themselves to become better writers, the way good Horror becomes great Horror.

Are you up to the challenge?

References

Adler, Mortimer J. and Charles van Doren. How to Read a Book: the Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. New York: Simon & Schuster, c1940, 1972.

Foster, Thomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor: a Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines. New York: Harper Perennial, c2003, 2014.

Prose, Francine. Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them. New York: Harper Perennial, c2006

Am I up for the challenge? Good question, KC!

I appreciate the timeliness of your article. Reading as a writer is what I’m trying to accomplish with my Summer Reading Challenge.

There’s a horror novel among the books I’m reading. A contemporary novel for a change instead of classics, I usually read. I’m hoping to learn about how today’s horror deals with universal themes and provide a fresh spin.

Of course, reading as a writer applies to all genres. And as readers, we’ll be rewarded for thinking, indeed. Thank you for another brilliant write!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re most welcome, Khaya! I think it ultimately came as a surprise to me that even knowing how to read did not exclude me from needing to learn all the ways language COULD be read! But once I started catching on, creative Muse-doors started opening and the challenge was on! I hope this post helps other writers see what we’ve all been missing…

LikeLike

KC, once again, you have written a compelling essay. I have to ask again–are you considering a book on horror?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Professor! I am always considering it…it will probably happen one day….

LikeLike

Reblogged this on charles french words reading and writing and commented:

Here is another excellent post on horror from K.C. Redding-Gonzalez!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for forwarding the propaganda!

LikeLike

KC, once again you are writing something that mostly, heretofore, has not been articulated in such away to make one realize that reading Horror novels as a serious way of learning better writing skills is so important, because it is the only genre that specializes in developing intense tension, keeping it’s readers on the edge of their seats, knowing all the while that it is a Horror novel they are reading. This type of writing must be believable in order for horror to work, and that takes mega writing skills. Thank you, KC – Awesome writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are most welcome, K.D… and I say that tipping my hat to your own mad skills!

LikeLiked by 1 person

KC, I am so honored by your compliment…Wow! You just made my day, week and so on…! Thank you so very much. Karen 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on K. D. Dowdall and commented:

KC, once again you are writing something that mostly, heretofore, has not been articulated in such away to make one realize that reading Horror novels as a serious way of learning better writing skills is so important, because it is the only genre that specializes in developing intense tension, keeping it’s readers on the edge of their seats, knowing all the while that it is a Horror novel they are reading. This type of writing must be believable in order for horror to work, and that takes mega writing skills. Thank you, KC – Awesome writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And thank you for the reblog!

LikeLike

KC, excellent post – I agree completely. I read classic writers of ghost stories growing up – I was drawn to stories by M. R. James, E. F. Benson, and other English writers. I also read and re-read H.P. Lovecraft. Later, I discovered Peter Straub and now I like the excellent horror novels of F. G. Cottam – and these days, I write ghost stories myself. I’m sure that absorbing and studying the work of these fine writers influenced me on many levels. Your discussion above was helpful and of great interest! Thank you for posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ghost stories remain one of Horror’s most consistent reader favorites…Too bad so many of us have convinced ourselves that the existence of a ghost and what it may represent is just not good enough alone as a device to scare us anymore. I think we are telling fibs to ourselves….ghosts still give us the creeps or we wouldn’t hide behind electricity!

LikeLike