As new biographies and Critical works and essays are published, more and more people are learning the awful truth about H.P. Lovecraft – the man ascribed to be the Father of the Modern Horror genre – that he was a racist, classist, arrogant bigot and misogynist.

In a world where we are increasingly affected by the consequence of such views, where do we draw the line? Where should we draw the line? And why – because of his contributions – do we seem so willing to look the other way?

What makes Lovecraft different? And how can we look to Lovecraft as a creative example with all of the things we now know about him?

The answer is complicated. But for those who recoil in disgust or offense, there are very important reasons why Lovecraft cannot be damned for his faults. And while we may wish to condemn him for his offensive-yet- period-driven personal views, if we are wont to do so we must also look at his own personal arc of growth.

The lesson is this: once we open the door to weighing an author’s work based on his or her personal life, we must include the totality of that life.

The Literary Defense

For those who dislike Literary Critics for seeming arbitrary in their judgments, Lovecraft seems the perfect example of the divide between Critics and fans of the genre. Have they not dirtied their hands and sullied their reputations elevating the creative status of a man who was not shy in his contempt for almost everyone else?

Lovecraft himself makes it easy to think so. As Charlotte Montague states in her biographical work, HP Lovecraft, the Mysterious Man Behind the Darkness, “Indeed racist sentiments can be found in his stories. ‘The Horror at Red Hook’ – described by the English fantasy fiction author [and Literary Critic], China Mieville, as ‘extraordinarily racist’…going further in my opinion than ‘merely’ ‘being’ a racist – I follow Michel Houellebecq…in thinking that Lovecraft’s oeuvre, his work itself, is inspired by and deeply structured with race hatred…” (Montague 101)

Make no mistake: this is not a maligning of Lovecraft, but a fact he himself boldly advertised in his own words and letters, confessing to being “known as an anti-Semite” (despite having married a Jewish woman), and displaying “contempt and even disgust for black people…Asians, Arabs, Mexicans, Italians, the Irish and Poles…” (101)

Yet such a reprehensible man sits at the top of our genre…

Do we not have an obligation to question why we select the people we do to elevate by excuse? Is this a case of “the end justifies the means”?

Surprisingly, the answer is no.

And a great deal of that answer has to do with Lovecraft himself – a man who “derived greatest pleasure from ‘symbolic identification with the landscape and tradition-stream to which I belong…” (Joshi 216). He was therefore a man caught in the constrictions of his own race and class at the time, a man whose search for understanding led to tremendous attempts at self-education and philosophical thought, whose own views changed during his relatively short life. This meager transition of personal growth (which some may see as underserved and inadequate), has importance in the Literary Critical scheme of things. Because an arc is an arc…

While we can recoil in disgust or “enlightened” superiority at many of his early enunciations against other races and classes, we also must acknowledge that we ourselves live in another time; we cannot know the struggle he might have had to understand his own world in the context of his personal, yet tightly shaped world view. Yet the needle did move.

For example, according to S.T. Joshi (todays’ most erudite scholar of all things Lovecraft), “Initially, Lovecraft felt that a frankly hereditary aristocracy was the only political system to ensure a high level of civilization” – an important observation when “in his preferences for political organization, Lovecraft again made it clear that the preservation of a rich and thriving culture was all that concerned him.” But during his lifetime, he did in fact begin to change, leaving fascist views behind “…as the prosperous twenties gave way to the Depression of the thirties, he began to realize that a restoration of the sort of aristocracy of privilege, cultivation, and civic-mindedness advocated (and embodied) by Henry Adams was highly unlikely, in the days of labor unions, political bosses and crass plutocrats of business who did not have sufficient refinement to be the leaders of any civilization Lovecraft cared about. The solution for Lovecraft was socialism.” (Joshi 217)

This one example reveals the simple fact that Lovecraft explored his own theories of not only what classes of peoples constituted “civilization” but how it should unfold during his brief life. We cannot know where his unrealized contemplations and potential epiphanies would have taken him; we simply know that he was a person whose ideas were in constant transit. We simply have as evidence an abbreviated life’s peripheral writings like correspondence and essays in which to frame his writings.

Should we then be privy to that private journey? Some Critics say yes, some say no.

But whether we do look at the private side of Lovecraft or not also can be said to have less direct bearing on his body of Literary work. Its total impact on the genre is not about his personal views but his world view as depicted BY his work…not so much about race as about humanity’s futile place in the cosmos. And while his personal views certainly “color” how he depicts this world view, it does not serve any greater purpose in his writing.

For Literary Critics, the reasons for this have more to do with what Lovecraft does with his writing that makes him what he is within the future Horror canon. The changes he makes there are Literary changes.

Again, we must remember that Literary Critics do not read for Criticism in the way WE might do while on vacation at the beach – the way we do every day. This is not “rationalism” but a reality. Neither is it the sign of a dog whistle – which is never heard if one is not a dog.

We read texts at face value – as fun romps through Horror universes. We are not seeking out double entendre, hidden meanings, subtext, or moral messages. In fact, we used to cede that intermediate ground to reviewers, who would point out details that made us sigh, “oh yeah…neat…” and triple our admiration of our chosen authors. Now we simply read in abject ignorance.

And we can do that with Lovecraft, seeing only the surface story. Lovecraft made such intriguing monsters – so many of them derived from real-life night terrors he experienced as a child – some still so reeking of childish imagination that we can easily identify with them– like the monster described as a mass of cosmic bubbles and sometimes seen in streams…Yog Sothoth… And for many of us any further allegory to racial superiority or class superiority is lost on us; we are indeed too obtuse to see it, too untrained, too not-caring.

It is easy to be bewitched by both monster and story… we identify with them without seeing anything nefarious, without suspecting too much in the way of bigotry or misogyny, forgetting our indoctrination by period pieces like Disney princesses because we are in fact indoctrinated…

This is not always part of a subversive plot, but more a matter of sociological evolution… we are all victims of our times – Lovecraft being no exception – and it is hard to clearly see something so thoroughly incorporated into our culture that it seems like this is the way it always was…like it has some divine endorsement.

Shaking loose of that takes generations. So when Literary Critics are faced with someone who so reeks of his time period that we can be properly “taken aback” at his “normalized” view of his fellow human beings, at his atheism, his love of Classic history, at his embrace of the scientific and the promise of astronomy… they see time capsules. And while we can cringe in discomfort at what a man like Lovecraft really, truly believed about his fellow human beings, we can also see the world he was living in.

Lovecraft in His Time

It always sounds like an oversimplified, if not convenient excuse to say, “he was a product of his times.”

But we need to acknowledge that the further back in history we go, the more this is true. We are spoiled today with access to information – to such an extent, in fact, that we have little sympathy for those who think in narrow ways, because we cannot imagine what it is to live in small, isolated, rigidly contained islands of carefully constructed and forcefully maintained social hierarchies. Perhaps a brief recollection of high school would be helpful, because if we think our own times do not contaminate our beliefs, then we are fools.

Yet we do have to look at that – at what surrounds a writer or an artist when they are creating their life’s work – especially if we are threatening to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Lovecraft was a sickly child of failing upper class parents. Early in his life, his father suffered from a “psychosis” ascribed to syphilis by some, dying when Lovecraft was a toddler. Lovecraft, however, would claim his death was the result of a “paralyzing stroke.” The loss of his father and his father’s income resulted in he and his mother removing to the Phillips family estate, placing him under “the smothering attention of his mother and two aunts, his grandmother, and the maidservants… (Montague 15) With the death of his grandfather at age five, he began having night terrors, suffering what he called a “near breakdown” in 1898 and another two years later…Students of his life have in fact suspected he might have also suffered from Asperger’s Syndrome as well , as he showed a number of known symptoms such as antisocial behavior, reluctance to leave familiar places, etc. (26) At times exhibiting signs of depression and suicidal thought, he was frequently plagued with intolerance, insecurity, and “nervous fatigue”… (34)

People do not live in vacuums. We have families and circumstances unique to ourselves. But we also are ships on our own cultural oceans.

And if we are going to weigh the soul of Lovecraft, we must also look at the culture that was influencing him; it does not exclude him from being an often reprehensible, unpleasant creature, but it just might explain why Lovecraft successfully exploits the fear of the Other without being an instigator of it. In Lovecraft’s writings, his racism is used as setting to fuel “fear of the unknown” and “fear of invasion” and “fear of something without conscience.” Had he been alive in the 1980’s, he might well have written a literary version of Jaws….

“Life is a hideous thing, and from the background behind what we know of it peer daemoniacal hints of truth which make it sometimes a thousandfold more hideous.” – H.P. Lovecraft

No, we cannot escape the impact of a writer’s experiences on his writing. Sometimes our own culture informs our writing, and sometimes it confirms our own terrors so that we write with a perceived, implied authority – convincingly… and in ways that span lifetimes. It does not help our case if we write stories published by our own, read by our own, judged by our own and preserved by our own.

Indeed, a whole lotta Lovecraft resonates with disenfranchised white males today. And here is an example of the how and why any buried dog whistle – that institutionalized dog whistle inserted by rote in his works – might sometimes have that particular sociological effect. But what should concern us here as we judge Lovecraft the man, is that it shows no evidence of ever having been meant to.

In preparing for this post, I was immediately struck by the truth of how shaped we are by our peers when I happened across these two paragraphs while reading The Trial of Lizzie Borden: a True Story by Cara Robertson. And while that real-life Horror story does not sound like it would hold any relevance, keep in mind the Borden drama took place a mere 18 miles to the southeast of Providence and some 200 miles east from New York City, sharing by proximity the same social Petrie dish…

“In this era [1892 for Lizzie, Lovecraft—1890 to 1937], America derived its vision of the criminal classes from European models of criminality… [Cesare Lombroso, a leading proponent from the Italian school of criminology] drawing upon contemporary anthropological studies of ‘other races’…believed the physical structures of their bodies displayed their criminal natures… ’he is like a man who has remained animalized…’” (Roberston [25])

and

“In one of her popular lectures, the prominent suffragist [my emphasis] and temperance advocate, Mary Ashton Rice Livermore contended: ‘an invasion of migrating peoples, outnumbering the Goths and Vandals that overran the south of Europe, has brought to our shores a host of undesirable aliens…Unlike the earlier and desirable immigrants, who have helped the republic retain its present greatness, these hinder its developments. They are discharged convicts, paupers, lunatics, imbeciles, peoples suffering from loathsome and contagious diseases, incapables, illiterates, defective, contract laborers, who are smuggled hither to work for reduced wages, and who crowd out our native workingmen and women.” (Robertson [26])

How amazing (and disappointing) when we are faced with the fact of how little our political rhetoric has changed…even as our targets have changed, as evidenced again by Robertson:

“…Large influxes of immigrants into Fall River – mostly Irish Catholic, French Canadian and Portuguese – altered the composition of the city in the course of the nineteenth century…Irish Catholic and English immigrants comprised the majority of workers in the textile mills by 1850. By 1885. French Canadians were the most important single ethnic group employed in the region’s textile industry…Each of the city’s social groups inhabited distinct geographical sectors. The segmentation into ethnic ghettoes paralleled the pattern of settlement in other industrial New England towns of the same period…” [20-21]

This means that Lovecraft – despite what appears in his work as uniquely bigoted and racist and misogynist – was a social conformist in his time; he was not alone in his prejudices and suspicions, which were at the least regional and publicly reinforced. The fears of the sociological moment fanned his own, and did so at such an extent that those fears are inseparable from his work.

But it is also a unique characteristic of inherent and institutionalized racism that the arrogance of the moment leads to the assumption that all people of reason, all people of your own class – agree.

So there is no preaching to the reader evidenced in his writings, because in Lovecraft’s mind, only white males like him would read and assess his works and any dog whistles were naturally, subconsciously infused with no conscious effort: Lovecraft’s intended audience was mostly himself and those like himself. There was no need to explain or recruit. He simply “reported” his observations and documented his fears.

It doesn’t mean that there are not images or allegations within his stories that now rub with the intensity of a Black Lives Matter moment… but they are more like Disney films…like the horribly racist drawings meant to be amusing in those wink-wink-nod-nod ways that are so clearly institutionalized racism today that we can finally see what minorities and Others have been telling us for centuries.

No doubt Lovecraft could not have seen the forest for the trees; he was far too self-centered, too paranoid of all outsiders, of all people he deemed not his equal – which his peers acknowledge was pretty much everyone else.

But it also means that Lovecraft probably could not help himself, either. He wrote the world as he – a white male whose wealthy family lost its wealth and who needed a reason to explain his own misfortunes, turned to other white males to establish an acceptable reason. He found it in racism against immigrants and people from other classes… including women, who at the time were often ghosts in their own lives. Continues Robertson on this matter:

“In the words of a contemporary journalist Julian Ralph, her [Lizzie Borden’s]situation exemplified ‘a peculiar phase of life in New England – a wretched phase’ suffered by ‘the daughters of a class of well-to-do New England men who seem never to have enough money no matter how rich they become, whose houses are little more cheerful than jails, and whose womenfolk had, from a human point of view, better to be dead than born to these fortunes…” [24-25]

As any writer can tell you, the best stories come from the singular place in self where real fears are harbored. Lovecraft mined terror from his personal nightmares, his personal dread of women and immigrants, his awe of the universe, his doubt about God, his loss of wealth and standing and the struggle to cover it up, his need for his talents and efforts to be recognized if not valued, and the irritations that come with native bigotries – close proximity to people abhorred, sounds of languages, smells of foods, suspicion of religious practices, constant and inescapable human presence.

Once again, we have to look at Lovecraft closely…to see that much of his behavior – while blatantly racist – also masked what was probably a host of antisocial if not psychiatric disorders.

It was a perfect storm of sorts for concocting his monster mythos replete with sinister, exotic characters. We have to “own” the social messaging of the times before we can shrink from Lovecraft and his flaws. We have to see the context – even if in Lovecraft’s case it is because he so impacted the genre…

Again, this may feel far too much to be like we are using the lexicon of Literary Critics. But in this case they are correct. And the more our skin crawls, the more we need to see why they are right.

It was not only natural at the time to believe the immigrant mythologies created by frightened white people, but it was white people who controlled all media, all “official” and socially acceptable behaviors – like moving white households uptown, and passing rumors about Other cultures downtown so not-understood.

This provided a ready-made foil for Lovecraft to terrify his characters with – cultured, upper class men lost among exotic (immigrant) cult worshippers, and rural-therefore-dark and ignorantly populated (lower class) settings to seat his creative world in. In a time where “science” was looking to explain human inferiority in animalistic terms, where fear became revulsion and an almost psychiatrically derived aversion to Others, prejudice takes on a frightening life of its own reinforced by mainstream culture. These are all the ingredients a Critic can dream of. And they were the very real interpretations of the ruling class – well-to-do white people – at the time.

But do those facts exonerate Lovecraft, once it becomes impossible to not-see the truth?

As reprehensible as it might feel, the answer is yes.

Seeing What We Want To See

Sometimes it feels like the bigger question is: do we all have our own motivations for seeing what we want to see when we look at Lovecraft?

And to some degree we do. Critics are as mesmerized by his writings as we are – so much so because for the first time they have the whole butterfly under glass – one whose life is documented, whose influence on a genre is indisputable and profound and authenticated, who provided so much information that can be used to analyze not only invention of story and impact of society on writer, but on the creation of genre…something that happened previously in the anonymity of indistinct pasts…It is the Literary equivalent of getting to see the Big Bang. They are – in a word – dazzled by the prolific collection of cross-pollinating information never before succinctly gathered in one place.

Yet for those who want to see just another angry white male, they will find plenty of evidence speaking to that – plenty of imagery that seems to reinforce that very institutionalized racism and misogyny we know we need to fix right here in our modern world…And those who just love a good mythos can get lost on a stormy afternoon as well…

For genre readers in general, there will always be some semblance of separation of author and intent, a blissful ignorance of what motivates the Horrors he or she writes about. We have come for the thrills, for the entertainment, for the escape. There really isn’t any subversive motivation to our willful blindness.

Again, when we read Horror, we read at face-value…

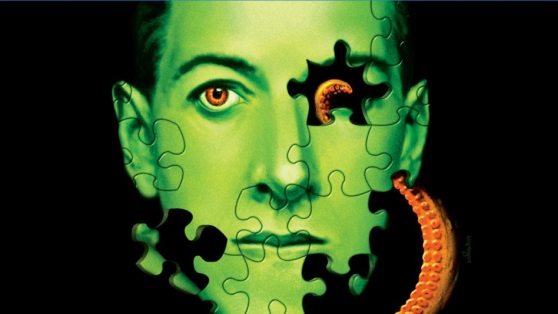

But we cannot escape Lovecraft’s influence. Lovecraft brought us a refinement of The Weird, he delivered us to the Literary Critic; he gave us the tentacle, and reconnected us to our English Literary roots via Dunsany and Blackwood. He opened the door to the unholy marriage of philosophy and Horror, of science and monstrosity, stretching the supernatural into the unknown cosmos.

Most of us are neither privy to nor interested in the man or his motivations. We fall in love with the monsters, the mythos, the scope of the dream worlds, because they resonate with us – not because of latent racism in ourselves, but because we are looking superficially at the monsters. We are fine with engaging in a shallow way with the decorations on the page.

In fact, we prefer not to see them… we don’t want our vision of Lovecraft or his writings sullied or ruined. Besides, we would then know we would have to ask ourselves that if we enjoy them…does that mean WE are racists, too?

The surprising answer is no. Sometimes a monster is just a monster… a cigar, just a cigar.

It really does depend on what level we are reading on…

Institutionalism from the inside is hard to spot and easy to rationalize. We might then wonder if we are doing that with Lovecraft – rationalizing for the sake of the genre’s Literary gain, and wonder further if we should be subsidizing his work, calling him the Father of the Modern Horror genre, emulating him, etc…

Indeed, Lovecraft is perhaps THE representational argument for debating the relevance of an author’s life and views on his or her work – should an author and his or her life be considered in Literary Criticism?

This is part of the big upheaval we now see in the field of Literary Criticism, where the discussion has great relevance. And I think – especially when one sees the volume of evidence and peripheral information on the life of Lovecraft – that there can most certainly be importance in Literary Criticism steeped in that author knowledge. But I also think that what cannot be applied to all authors should not be applied as a general rule of Criticism… knowing the details makes his case so very different from others and there will always be and have always been authors about whom we know precious little.

Lovecraft is that rare exception.

And through the lens of Literary Criticism, Lovecraft rises bereft of racist promotion. Rather, it is a geographical feature in his work, an accent, a layer of setting. His World View, in other words, rises free of his own prejudices to question the purpose of humanity among the cosmos…Incredibly, Lovecraft is more about religion than race.

But why, we ask, do we not penalize Lovecraft?

Again, the difference is that Lovecraft ‘s works do not preach his bigotries – but reflect them – and which are unfortunately, a product of their historical times. What we know about Lovecraft is there because other people noted and kept those details, not because of some arrogant plan for infamy and immortality; he wrote letters to acquaintances, not manifestos.

That he also did things never done before in our genre is what makes his contributions irreversible and inseparable from modern Horror fiction.

Lovecraft’s morally dubious quality of racism remains unavoidably burdensome and is not attractive, and neither was his arrogant classism. But we are stuck with him. Because there is absolutely no avoiding him or the impact of his work in the Horror genre.

So here is the truth: Lovecraft is a one-man branch of Horror tradition who represents a mere moment in time but also an incredible leap in philosophical Horror; where we go from here we go because of him or in spite of him.

But we go in his shadow. It’s time to get familiar. We don’t have to like him; but we cannot and should not ignore him.

References:

Bilstad, T. Allan. The Lovecraft Necronomicon Primer: a Guide to the Cthulhu Mythos. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, c2009.

Joshi, S.T. The Weird Tale. Holicong, PA: Wildside Press, c1990.

Montague, Charlotte. H.P. Lovecraft: the Mysterious Man Behind the Darkness. New York: Chartwell Books, c 2015

Robertson, Cara. The Trial of Lizzie Borden: a True Story [Advance copy]. New York: Simon & Schuster, c2019.

I often wonder what would have happened if he had lived a bit longer. When he moved back to Providence after living in New York for a time he noticed that even Providence had changed and he began to travel and see other parts of America which I think had a great influence on him. I’m mindful of the racist and misogynistic man he was, and yet it never stops me from reading his work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree. My own rationalizations for still liking his work despite knowing what I knew seemed contradictory… So I set out to understand why he is not roundly condemned, and despite all remains one of the genre’s most respected writers in lieu of his blatant racism. I found the answer in Literary Criticism and thought it might soothe the ruffled feathers of fans who feel compelled to defend him but know neither how, nor why …Hence I decided to shared the Critical rationale.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I wrote an article about him last year which was greatly influenced by the documentary Lovecraft Fear of the Unknown. That documentary is quite good and has writers like Neil Gaiman sharing their thoughts on Lovecraft.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That said, my article wasn’t as good as yours.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for such a thoughtful essay and one that’s so meaningful in today’s cultural moment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re welcome! I think todays’ cultural moment made it possible to ignore any further… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

When you said, “made it possible to ignore any further” did you meant to say “made it impossible to ignore any further . . .”? I’m confused.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes…”impossible” is the right word…great editorial catch Monique! Thank you for helping me clarify! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose at the end of the day you have to look at the work apart from the writer. There are several whose attitudes I disagree with, but the work is admirable. And everyone is a creature of their time. He’s a very interesting writer.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I agree — And I think he also represents a “teachable moment” for all of us needing to get in on the discussion and understand Criticism as well..

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’ve taught me things I didn’t know about Lovecraft. I wonder what his stories would have been like if he even lived just one more decade. Fabulous post!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fortunately there is a veritable wealth of information on the man and his life…a most interesting person (if unlikable). He set so much precedent in how to be a good Literary-minded writer as well, emphasizing the importance of staying true to your own artistic vision, self-publishing, joining writers groups, and his work with the United Amateur Press Association to name just a few.. I recommend anything by S.T. Joshi for those who want to dig deeper…

LikeLiked by 1 person

KC, thank you for an excellent article on a very difficult subject. This is something with which I have struggled regarding several writers, and it is an issue that must be confronted. For me the line that cannot be crossed was with the poet Ezra Pound, a blatant supporter of Fascism. I refuse to read or teach Pound in my classes. With other writers, we must make our determination of time, place, and society. Excellent work!

LikeLiked by 3 people

It is a difficult subject, separating artist/writer from work. But I seriously believe Critics are onto something with Barthes and the whole Death of the Author thing…It simply gets harder the more we know about the biographies…Drawing a hard line may well remain a tricky and flexible thing…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on charles french words reading and writing and commented:

Here is an excellent and thought provoking article from K.C. Redding-Gonzalez, whose writing is always on the highest level.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Professor!

LikeLiked by 2 people

KC, you are very welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovecraft was a man deeply afraid of the outside world. You can see this in the way he lived as well as the content of his work which usually dealt with themes of outside forces closing in on the heroes. I greatly enjoy Lovecraft’s work, even if I have very little love for the man himself. Usually I’ll separate the creator from the creation.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is indeed what many Critics have decided must happen for honest and impartial Literary Criticism…It makes sense, because none of us will be around to defend or explain our work — that job will fall to the work itself. And as such, does not the author become irrelevant? A hard question…one today’s Literary Critics are debating. Thanks for the insightful comment…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s interesting to read certain writers from a modern viewpoint, with the analytic tools and comparisons we have at our disposal, and still realize that, even if they were writing as a reflection of the time they lived in, it still doesn’t truly make it “ok.” Lovecraft being one whose work exemplifies this, as you express so eloquently. Yes, context is always essential in understanding an author and a book, but as an example, I’ve read the book “Gone with the Wind” numerous times and though I enjoy it as literature and understand the concepts, it doesn’t make slavery right. Excellent and thought-provoking post, as usual.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for the compliment! Indeed what is equally alarming is how long it is taking for us to just say so…as though admitting the misstep invalidates the accomplishment. There are many roads to greatness; it’s time we starting picking better paths…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating post.

I must agree with your conclusion about Lovecraft. In fact, if you look long enough, you’ll find something rotten in anyone’s biography. Check out these two statements:

“Anyone who has traveled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European and American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results.”

“I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races from living together on terms of social and political equality.”

That wasn’t Lovecraft who made those remarks, but Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Life remains messy… One can only hope that we leave behind a legacy of trying to be better human beings, because chances are, we have all screwed up a time or two even with our best efforts to be enlightened! Thank you for the comment and the quotes. It just goes to show that even the best of us always have room to grow!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the reblog, Vincent!

LikeLike

Even more extraordinary analysis from you, KC. “A blissful ignorance” is what I have about most writers of his day… I list historians in this category. The writers were also blissfully ignorant and sold us lies. ( I just tossed a book from 1968 – it made me want to scream.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do believe ignorance about the author has its benefit in fiction — a reason perhaps that I now firmly ascribe to the Critical position that a writer’s work should stand on its own merit and apart from the details of the author’s life. In far too many cases we would be left with nothing to read if we judged all works by the flaws of the person who wrote them — instead of the message within the works themselves…As for history, sometimes an author is hampered by their own access to information; but we must be mindful of those who see documenting history as part of their personal “duty” to obscure unlikeable facts, and for that reason history writers do indeed need their credentials to write it exposed fully. We should be forgiving of those who are ignorant by circumstance — not so those ignorant by choice. (I know I have found some historical accounts that were for example meant to be insulting to Native Americans — when in truth, the accounts showed how very savvy and accomplished their fighters were…sometimes it is how we look at things!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting, KC.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An interesting writer makes for interesting material….:) I feel like I cheated!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You didn’t. You just opened a door to a writer. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Insightful and interesting, KC. I knew little about Lovecraft. Thanks for this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Debra! Lovecraft is the Critical gift to the genre — onion layer after onion layer. But he is also intriguing for how his dedication to his own concept of craft sets a solid example for the rest of us. It is that nuance of Lovecraft that I find most interesting and most useful for modern writers seeking a way to survive and hone their own storytelling in a harsh, unfriendly publishing environment… Some good lessons among the prickly ones…

LikeLiked by 1 person