In the example of Bram Stoker we see how a writer makes sense of a pandemic when he or she is a witness to the event. With King and Matheson, we saw how a writer imagines living through the event. But what if pandemic actually claims someone you love?

Horror has two prominent writers whose lives were touched by such a personal loss in profound and painful ways, tearing at their very souls to the point that they did not so much choose to write about it, as much as they were tormented into doing so.

Both Edgar Allan Poe and Anne Rice lost close family members to the unthinkable: Poe repeatedly lost the women in his life to disease – most commonly tuberculosis, a pandemic that seemed unstoppable and endless in his lifetime. And Anne Rice lost her daughter to a new kind of pandemic: the kind that goes undeclared because the contagion of it is not that of more familiar viruses and flus, but because they ravage our population as silent killers, misunderstood and curiously accepted as they pick us off one by one. With Rice, we are talking cancer – not your typical pandemic disease, but one which by its numbers seems to indicate an undeclared epidemic, one with multiple yet universal origins. But just in case you were wont to dismiss it in the face of the coronavirus, understand that no less than eight viruses have been linked to causing or contributing to the development of cancer.

Poe: Masque of the Red Death… and Everything Else He Wrote

Everything that came from Edgar Allan Poe’s pen reeks of premature death, decay, and the decomposition of life – sometimes (as in the “Fall of the House of Usher”) of culture or literal ways of life. Poe was not born of privilege, nor was he ever far from experiencing the judgment of class and condemnation of his contemporaries. Born the child of two actors (not considered a reputable profession at the time) on January 19, 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts, “a city that later in life he would loathe” (Montague 12), his was a life of struggle and loss. Disease dogged his every ambition.

Yet we in Horror hold him particularly close, especially in the United States, because he was the first to remake Horror we knew as definitively British into something local, and organically American. He translated Horror for us, and helped us see the futility in repurposing folklore without nurturing native roots. He became the most Literary and most original of our Horror writers…and he was the one H.P. Lovecraft (the presumed Father of Modern Horror) declared to be the most influential writer for him. (Montague 172)

Historically, he strikes us as a sad, macabre figure, an addict and alcoholic whose craft with language was eloquent and lyric. Yet those works we read as twisted and carefully crafted into perfect Horror in some joyous creative act was (n reality) one writer’s response to both his own grief and the poverty that served as the machinery behind those diseases of mind and body that plagued his life. It is with Poe that we see perfectly embodied the very modern argument that poverty enables premature death, addiction, and mental anguish.

And it is also with Poe that we see something else we prefer not to believe happens even today: the very public criticism and judgment of his failings – from his personal ones to his professional ones – by the very people who should have been able to rise above their own prejudices, but who (like we do right now in modern times) chose to consider themselves his moral superiors and therefore immune from death by such disease as haunted Poe’s existence.

Tuberculosis was the pandemic of Poe’s short lifetime (1809-1849) – taking his mother when he was just a toddler, and no doubt fixing in his mind the effects of that terrible wasting disease on the human body as it steadily stole away so many of the vibrant women in his life. The effect on his poet’s mind was clearly profound – inciting fears of the presence of blood, of the imminent threat to the young and old alike, to the possibility of premature burial, and the pale, vampiric presence of his contemporaries.

Poe was poor. He was born into poverty and remained there most of his life. And he is the example of what it costs us as a society to dismiss the poor to the association that it is the result of something that they have done to themselves (i.e., failure to just “do” better, to work “harder,” to have proper “ambition”) that blocks their pathway to the right to health, and the fault or responsibility of no one else. It is during his time that we cement our modern view that the poor somehow “deserve” their fate, that the poor are “dirty” and purveyors of mental illness and disease, that there is just naturally something “wrong” with them and disease is merely nature’s unfortunate way of weeding them from the herd.

With the rise of epidemics like tuberculosis, we cemented our belief that disease is caused by improper morals and “questionable” behaviors, facilitated by immigrants and undesirables filling boats that deliver them to our pristine American shores. Alcoholism and drug abuse was rampant then as now among the impoverished (even as it was “discreetly” indulged in by the higher classes). Yet by social design we intentionally disregarded the clear connection disease and addiction made between poverty and health, length and quality of life – despite the message being trumpeted by cherished writers of the time like Charles Dickens.

In fact, we have exercised our discrimination often disguised as “precautionary” action against disease – disease being something all people fear equally, and the rich and bigoted can use to exclude Others from the American Dream. We have to look only as far as our immigration practices at Ellis Island, right in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty:

“From 1892 to 1924, about 12 million people from other countries arrived at Ellis Island in New York. Those in steerage were subject to health screenings by physicians from the U.S. Public Health Service. The doctors checked for trachoma, an eye disease that often led to blindness, and watched for other conditions. The process could take anywhere from three to seven hours. Female physicians conducted some of the immigrant screenings on women who were modest and not comfortable undressing before a man…About 1 in 5 arrivals required more complete assessments, and those deemed a risk were quarantined at the Ellis Island Hospital, which closed 60 years ago and recently opened for limited public tours….Nurses cared for the 1.2 million patients suffering from heart disease, measles, scarlet fever and other conditions. Those considered infectious were placed on the wards of the 450-bed Contagious Disease facilities, on the farthest island from arriving immigrants. Those with mental illness were held at the 50-bed psychiatric facility until they could be deported. About 355 babies were born at the hospital, and 3,500 people expired during their quarantine….” http://essynursingservices.com/ellis-island-immigrant-screening-and-quarantine-is-nothing-new/

Did it pass your notice that it was steerage passengers who were subject to screening? As if the wealthy could not, would not, or were morally immune from carrying disease. Steerage was where passengers with the cheapest tickets would be kept (and that would mean simply The Poor). This was the world Poe was living in… as a poor person, an alcoholic, an addict, and one often simply thought of as “mad.” And we live in similar times now, where both the poor and immigrants are seen as the harbingers of pandemic… Do we not at times feel made a bit “mad” ourselves?

Today we still see this “screening” happening, albeit in different ways. We denounce Others as immigrants first by anticipated moral failings (“rapists and murderers”) because being likely not-Protestant doesn’t work to scare a nation torn between agnosticism and evangelicalism. But if that fails, we resort to “dirty and diseased.” Take a peek at our current immigration policy as applied to our Southern border for proof…

We have long waged war against the poor. And it is a war we are losing as we willfully decimate the Middle Class to benefit the wealthy, disguising it as the failure of lower classes to properly educate and prepare themselves. We tuck it behind the Technology Revolution, implying when not outright saying it is related to an intelligence if not moral failing that certain people are being “left behind” and that it should never be the responsibility of successful Americans to ensure the education, health, and welfare of the poorest of Americans – especially if they are of color. We remain tone deaf to a subtext that has begun to push to the surface. And we can see from the life of Poe and Stoker that this has been baking in our national culture for quite some time.

This same attitude held Poe down: his reputation took hit after hit, the name-calling was venomous, the professional and Literary Criticism relentless in its moral condemnations of his alcoholism, drug abuse, and “unsavory” character.

Poe fought back – sometimes lowering himself to his critics’ level, sometimes rising above in stunning Literary Critical essays of the quality that impresses today’s Critics…

He was accused of plagiarism by novelist William Gilmore Simms, and engaged in numerous professional battles resulting in libel suits and “scandalous rows” marked by fistfights and public scenes (Montague 130-131). He had “questionable” relationships with women. Poe, caught in the web of grief and addiction, seemed unwilling if not unable to help himself. The worst was thought of him while his personal life was quite publicly ravaged by his addictions — clearly fanned by the staggering loss of women intimate to him to disease – especially tuberculosis. Poe is not, then, the best of examples as to how to turn pandemic loss into writing – but he is most certainly living proof that when Life happens to a writer of talent, magic might well be spun from the agonies that torment the grieving mind. He was also “the first American writer to support himself entirely from the proceeds of his pen” (76 Montague)…

Poe is proof that a writer cannot turn off the words meant to define life. He is proof that even attempts to drown or mutilate the Muse will not succeed. She will, instead, haunt us until we write what we see.

That Poe saw in his poet’s mind what can be seen as vampiric women is also not so unexpected, then, because they are a natural extension of what he saw as a child and experienced as an adult (much like that which affected Bram Stoker). But they are also a natural extension of what writers of Poe’s time witnessed in the premature deaths of women, seen throughout his works like Legeia, and “The Fall of the House of Usher”… both haunted by the notions of life after death and “an emaciated, dying woman…” (Montague 59)

That constant ravaging of his life and loves by death and disease are why we have his incredible writing. Writing through his emotions his images of pale, decimated women haunt us like few others, because they are rooted in truth and genuine grief, in anger and denial, and the cruel acceptance of a life he had no control over. “He died in a hospital, on Sunday, 7 October 1849, a sad and beleaguered end to an unhappy and harassed life. He was forty years old.” (Akroyd 190)

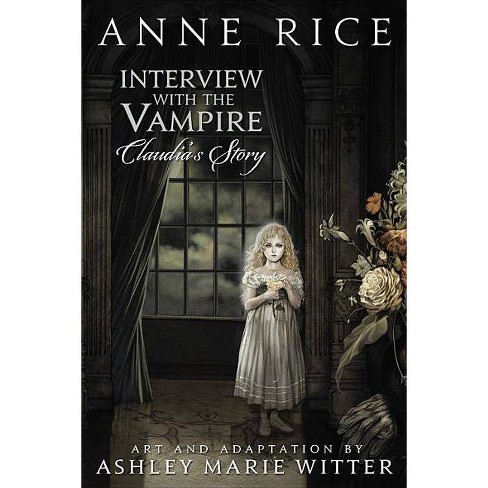

Death of a Child: Anne Rice and Interview With The Vampire

Born Howard Allen O’Brien October 4, 1941 (yes, Howard) in New Orleans, Louisiana, the woman we all came to love as the author of The Vampire Chronicles, Anne Rice, has single-handedly reshaped the Vampire in modern Horror.

Would it surprise you to know it was because of the death of her child that all of the right questions took shape in her books to elevate a good story to a Literary one? Would it surprise you that Cancer has a root in viruses?

For many of us, cancer is not a typical “pandemic”… it does not spread by contagion. It has a “routineness,” a “familiarity” for us… an expectation of survival in percentages. For modern people, cancer is a ghostly familiar – stalking us, devouring us, yet minimized by “treatments” and our own preferred ignorance of the disease within the lottery of our lives.

Yet is has been connected to viruses in our modern research of the disease. So maybe our early human instincts to shy away from those diagnosed with cancer had some preternatural sense at play. Or maybe we were just shocked and overwhelmed by the horrors this disease can deliver – and the terrors of the first treatments we tried to defeat it.

One has only to drift back to the 1960s and 1970s to see that it is there – in those decades – that we realized how prevalent it was to the human species, how terrible, how…fatal. Because we were better at identifying it at the precise time we were environmentally enabling it… cancer felt very much like a pandemic – so much so the common person even today still has trouble really believing we can’t “catch it” from each other.

Cancer is everywhere… quietly rubbing out vast numbers of us. Our governments are silent. Our researchers…struggling in what seems like competition with every other researcher for funds to find a cure.

But for many in my generation, the most vivid memory of cancer’s emergence into our mainstream consciousness is the pure Horror of random and horrific loss.

To understand where we were during the time Anne Rice was facing her loss, movies like Sunshine, Brian’s Song, and Love Story will give you a clear picture as to where we were in cancer diagnosis, treatment, and our loss ratios.

A cancer diagnosis was so horrific, friends and family often fled. And I can tell you that even in 1997 when my mother battled cancer, her friends and family (having clear expectations of what was about to transpire from those very films and life experience) … largely evaporated… rendered emotionally incompetent to deal with her dying, fleeing like her terminal diagnosis was…contagious.

It turns out, we come by this superstition honestly. According to an article in Healthline titled “8 Viruses That Can Increase Your Cancer Risk” “It is estimated that viruses account for about 20 percent of cancers. And there may be more oncogenic viruses that experts aren’t aware of yet.”

Whether we sense this or simply fear it, we cannot seem to help ourselves when it comes to treating cancer like a contagious virus, and its victims become inexplicably feared. Virus (to most lay people) means “infectious…transmittable…dangerous.” We are unwilling to believe we have such viruses resting dormant in many of our bodies as a part of simply living. We NEED – desperately – to believe we can control “catching” something as horrible as cancer. We need to believe we do NOT contract it because we were better, smarter, more faithful – and not because we were luckier. Cancer victims remind us we are living in a duck-shoot.

And here it should be said clearly that with regard to cancer-causing viruses: “Keep in mind that having an infection by an oncogenic virus doesn’t mean you’ll develop cancer. It simply means you may have a higher risk than someone who’s never had the infection.” And keep in mind that had to be said to assuage the fear the words both “cancer” and “virus” have come to embody.

Hence, I place Anne Rice here among the more traditional pandemic writers. Rice endured the terribleness of a cancer in her child at these early times in our attempts to understand, define, and treat cancer. And with her writing we see the evisceration of a parent trying in vain to save her daughter, to navigate the roller coaster of treatment and prognosis, to bargain with God for the life of her child.

Death changes everything.

And when it takes a child the parents’ world is turned inside out no matter what the era or reason, no matter what is happening in the rest of the world. Despite the almost routine commonality of child deaths until the late twentieth century which saw the development of medicine and discoveries of vaccines (and then even more so within the developed nations where privilege takes on newer and more insidious dimensions)… the death of a child seems always wrong – inverted, out of order, unnatural…

And to any who have experienced such a loss, the profound question of “why” is perilously pushed to the forefront, dragging God and religion behind it. We start asking the deeper questions – everything from why any God would allow such a thing to happen, to what does death mean, what role does immortality play in our processing of a child’s death, and even questioning ourselves as to why we go through a stage of bargaining with God before, during and after that child’s death.

The loss of Anne Rice’s daughter to leukemia shaped almost all of her writing. She handles depictions of children, of pandemics and epidemics, of mother-daughter relationships with a delicate yet firm hand. And once the knowledge of her loss is revealed, we read her works differently… we see… we understand….

In Rice’s most popular work Interview With The Vampire, we meet Claudia – a child Vampire whose immortality becomes its own curse. Here Rice has laid raw the quandry of every parent who has ever lost a child: what would you do to get them back? And if you got them back, how would they feel about being dragged back? Does death have a necessary purpose?

Rice tackles all of the big questions about death and religion. She does this not to prove her Literary worth, but because she is living those questions. She is asking those questions for herself.

This is why her work has authenticity. And authenticity is why we believe her Vampires, her stories… This is also why her characters ask the same questions she herself has – making them real… and dragging behind those are the other questions we initially mistake as the theme of the Vampire novels — the very real modern issues of sexuality and gender identity, of societal and cultural mores… issues we often see first because the heaviness of religious questioning opens unwelcome chasms in ourselves.

When we as readers first read Interview, we see the socio/sexual/gender issues immediately and we think “how brilliant!”… how competently she wields the Vampire trope to expound a Literary argument… Yet any reader/fan of Anne Rice will be haunted by one single character: the child vampire Claudia. She dominates. She scene-steals. And we cannot take our Literary eyes of her… There is a subtextual reason for that, but in many ways we are clueless without the detail of her personal biography. Claudia is a big red flag that there is something else, something bigger being hinted at by its screams from another room.

Here is where two things happen for Critics. Either they have to look at the author’s catalog of works to deduce the pattern of religious questioning regarding children and death, or they have to use biography to Critically fully assess the Literary values. Fans will likely read the catalog and possibly come to similar conclusions. But Critics will likely attempt to weigh and argue everything. (Again, this plays into the modern Critical debate about the use of details from an author’s life to weigh the success of their work.)

And then we as fans stumble across Rice’s biographical detail like so many Critics, and then we also see… the scales fall from our eyes… there is something much, much bigger at work in the writings of Anne Rice… necessary to sense the ghost of something much larger moving behind the obvious prose. It is not necessary to treasure Claudia, to elevate her to being a favorite character we are content to let argue subtextually the religious questions that surround the death of a child. We are content to let Claudia as a secondary character leave the questions poignantly pregnant and unanswered as they are to most of us in reality. Because these are the most unpalatable of questions. We are content, then, to distract ourselves….

Why did Rice (like Matheson and Stoker) also choose the Vampire? Which monster is more suitable to question the existence and motives of God? And how innovative to create contemplative, empathetic Vampires!

But was it artistic vision, or simply a mother’s grief?

When we know her biography, we see Rice had no real choice but to write her story the way she did. And THAT is the lesson of writing not only honestly, but writing through grief: the tale cannot be told any other way but the way it is. This means it is not so much a conscious decision about reinventing a monster in the genre – but a necessary means to tell the story that HAS to be told. That natural comingling of need and opportunity becomes genius. One can never read Anne Rice and feel that the story is contrived, because her questions are always sincere.

In her book titled Prism of the Night: a Biography of Anne Rice, Katherine Ramsland explains: “Had any vestige of Anne’s Catholic faith survived the death of her mother, her intellectual doubt, then her emotional crisis from years before, it was utterly destroyed now. The prayers of her family had been useless, empty. There was no God, or at least not one who cared. She rejected any heaven that demanded the sacrifice of a child – especially her perfect, beautiful little girl.

“Two years later she would put this loss into words through the character Louis [from Interview With The Vampire] as he said in despair:

I looked up and saw myself in a most palpable vision ascending the altar steps, opening the tiny sacrosanct tabernacle, reaching with monstrous hands for the consecrated ciborium, and taking the Body of Christ and strewing Its white wafers all over the carpet; and walking then on the sacred wafers…giving Holy Communion to the dust…God did not live in this church; these statues gave an image to nothingness…” (Ramsland 130)

Grief, made real, begets terrible truths about our own humanity.

And we can also never see the Vampire in the same way: we have to admit that it is the perfect monster for pandemic – forcing all of the right questions to the surface, dangling our innocent and naïve understanding of what immortality is all about.

The new question is: is it the only monster that can do so? Or is there one out there we haven’t discovered yet?

The Secret of the Best Horror Writings of Pandemic

So what can we conclude from the successes of these six authors?

Each one of them did not set out to write Literature in particular – just good Horror and good stories – and they used their knowledge of, fears of, worst imaginings of, and loss from death, disease and pandemic. For each one the weaving of genre Horror and Real Life Horror involved the supernatural…each to different effect, each with different degrees. All of them could not separate religion completely from the equation, because when humanity is faced with death on a large scale, human beings start looking for the reason in it, and the purpose of our lives if such are to be cut so unfairly short. And all of them danced with the Vampire if not the question of the presence and influence of Good and Evil itself.

The trick has been to balance the Horrors of Real Life and those Literary elements with genre tropes. We still see that struggle happening in today’s Horror, where the Horror often plays a losing role. It is difficult then, to frame reality with what so often comes to feel trite.

Yet do we not love both the monsters and the victims in all of these stories?

The very best of them allow us to read a work strictly as Horror, or as a Literary offering where Something Bigger is being addressed. We see that all-important double entendre brewing.

Did you feel the difference in the three who did it best – Bram Stoker, Poe, and Anne Rice? And did you do so because you almost felt tricked into it? You read the story, thought sincerely you were just reading a genre story of Horror, and when someone pointed out the author’s histories and the possibilities of what all was being discussed, there was an Ah-ha! Moment… one that reinforced that uncanny feeling you had when reading them.

That is how a work “becomes” Literature. It starts with the author’s personal experiences and fears…it is transformed by those fears into a mirror of Real Life whose Supernatural reflection anchors it within the Horror genre.

I say again that it is my opinion that details of the lives of authors should never be the determining factor in interpreting the work. It is, however, a long tradition of Literary Critics to examine those life-details, and a current debate within the field as to the ultimate importance in examining and analyzing a work for its place in Literature. Knowledge derived from author biographies and their intimate secrets of the lives of authors should only enhance their work for a reader or Critic. Those details should contribute to a reading of a work or an appreciation of how an author creates Literature. Those details should be inspirational to common readers and aspiring Literary writers, but knowing them “going in” can only shade and distort our expectations of the work – planting seeds the author never wanted visible, but merely sensed.

We have to ask: did they do that without us knowing the intimate details – the story behind the story? Or did we need the biography to decipher the Literary elements? Can we savor just the genre if a reader wants to?

How successfully this is done determines the value of the work as Literature. Too much Horror and Critics may see it as a mishandled mockery of Literature, too little Horror and the genre and its fans shy away. It is a delicate balance –but a necessary one to identify if new writers never taught about Literature and what Critics do are to come to an understanding and appreciation OF Literature – and even more so if we are expected to create new Literature.

What these works show us as uneducated readers and writers (that is uneducated in the ways of Literature) is that the Supernatural has to be more than hinted at, more than a prop – it must have an integral and working role in the story.

Horror should never be mere decoration, draped around a story to wedge it into genre: it should fit naturally. It should breathe.

So if we are to write some great, potentially Literary-level Horror during and after this pandemic, the lesson is that there must be authenticity in both the story and the Horror meant to tell it.

Imbue your monsters with Life – like Anne Rice (who changed our ideas about Vampires for us forever). Imbue your monsters with reality – like Poe did (by wrenching our terrors from our imaginations and having his characters live them literally). Imbue your monsters with the power of death – like Bram Stoker did (by letting the slow dread of creeping disease ransom our reason in our Horror of death). Imbue them with humanity — like Richard Matheson did (by drowning his protagonist in Vampires while battling the crippling Horror of human loneliness). Imbue them with cultural myth – like Stephen King did (by showing us that who we are as people determines real outcomes in times of pandemic, and that such is choice). And don’t date your work by too much name dropping and dated material that might necessitate rewrites if not later explanation – like Dean Koontz did (by proving our ignorance of the future can cause whole new interest and eager – if not misguided – reinterpretations of our work long after we ourselves have given up on it).

Knowing these things now… won’t you re-read “classics” differently?”

And more importantly, aren’t you inspired to try to write one?

REFERENCES

Ackroyd, Peter. Poe: a Life Cut Short. New York: Doubleday, c2008.

Healthline Newsletter. “8 Viruses That Can Increase Your Cancer Risk” retrieved on 6/25/2020 from https://www.healthline.com/health/cancer-virus

Montague, Charlotte. Edgar Allan Poe: the Strange Man Standing Deep in the Shadows. Oxford: Chartwell Books, c2015.

Ramsland, Katherine. Prism of the Night: a Biography of Anne Rice. New York: Plume, c1

Fascinating article. Interview with the Vampire is a profound work.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Rice is an amazing wordsmith and storyteller… I recommend her non-Horror works Cry To Heaven and Feast of All Saints as well…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating and very appropriate

LikeLiked by 2 people

And that is somehow a sad statement of our times…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed it is, regards JB

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great article!

LikeLiked by 3 people

(if not longer than originally intended!) And thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Again, again and again you are the most brilliant at analysis, KC!

Poe, oh I love that man.

…And we can see from the life of Poe and Stoker that this has been baking in our national culture for quite some time.

Yes, this is what we are seeing, again.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And yet I hope we are not just stirring in a fevered dream, but have at last begun to wake,,,

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great post. I love Poe’s works but now you’ve given me a deeper insight into why his writing speaks so truly. And, not related to ‘horror’ specifically but certainly to the ‘pandemic’ theme, I’m thinking of Boccaccio and his brilliant ‘Decameron’ (mid-14th century) which he wrote after fleeing Florence in the wake of the Plague that was decimating all of western Europe. His introduction to his marvellous (and bawdy) stories is an accurate and chilling account of the breakdown of social mores under the pandemic’s assault, and there are certainly some similarities to our Covid experience.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you for mentioning that wonderful reference! There are so many hidden themes in the shadows of Literature just waiting to be explored today — also showing how Literature never ceases to resonate with the human experience…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow! This is a brilliant, powerful post. We assume that the poor are carriers of disease. Poe was a victim to scorn, and you detail much more. I feel he is proof that the best writing comes from the deepest of emotions. Thank you, KC.

LikeLiked by 3 people

He is indeed for many of us….And reading his writing is often the very first time we encounter not only pure Horror, but we have our Literary fires lit as well — a subconscious script that stays with us afterward with every thing we ever read from then on…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said, and quite true!

LikeLiked by 1 person

KC, This is an excellent post, simply an extraordinary piece of writing! Thank you for sharing it with us.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you for bearing with the length of it… Sometimes a gal’s gotta ramble!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on charles french words reading and writing and commented:

Please read this excellent post from that wonderful writer, KC Redding-Gonzalez!

LikeLike

Thank you, Professor!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Jeanne Owens, author.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent, KC. Amazing analysis and it certainly makes me look at their work a little differently. I can’t wait to see what type of horror stories come out of this latest pandemic. The ethical questions, the demands for freedom and rights, the ‘COVID’ parties, the treatment of seniors, the confusion…so much to work with, and thank you for this insightful essay.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You are most welcome… Now if we can silence the Covid noise long enough to start toying with stories!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nice blog, amazing post

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

I prefer not to think about the author’s life as I read because I don’t want to bias my reading. Actually, if the story is good, I CAN’T think about the author’s circumstances because I’m too lost in the book. I could tell, though, with Chaim Potok that he had secreted illness in his family (turns out that’s correct). I didn’t know about Rice’s daughter, but I could tell from Interview’s Claudia that Rice had some kind of special connection with a young girl. Claudia does indeed still haunt me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I so agree with you about prioritizing the work over the author while reading the work… But where I find the author’s life important is AS a writer, trying to learn from other writers and understand how to place personal experience and honesty into a work without soapboxing, how to make personal experience into a universal one in the pursuit of Literature… in unravelling the mystery of invention…. Claudia is so the example of how that is properly done!

LikeLiked by 1 person