When we ask for names of female writers of color in the Horror genre, we (as the alleged Horror mainstream) might expect to hear two: Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison.

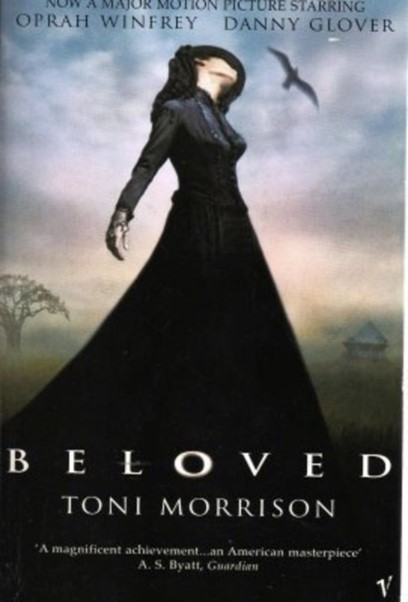

Yet we also expect to hear that Morrison only wrote one Horror novel (and that one so Literary that the only thing making it the least bit Horror is the ghost that animates its prose) and that Butler is really more of a science fiction writer.

Why do we do this? Why do we take certain works and decide that some anonymous Horror authority has plucked certain criteria from these writers’ stories and found them “wanting”? And is it any coincidence that this keeps happening to writers of color in our genre, and has gone retroactive in our judgement of writers from the LGBTQ community in Horror?

What exactly are we using as justification for exclusion of these writers from our genre?

Would you believe we dare to invoke Literary Theory?

Would you believe we have no such expertise or authority to do so?

There is an idiom at play here: if you can’t dazzle them with brilliance, baffle them with bullsh*t…

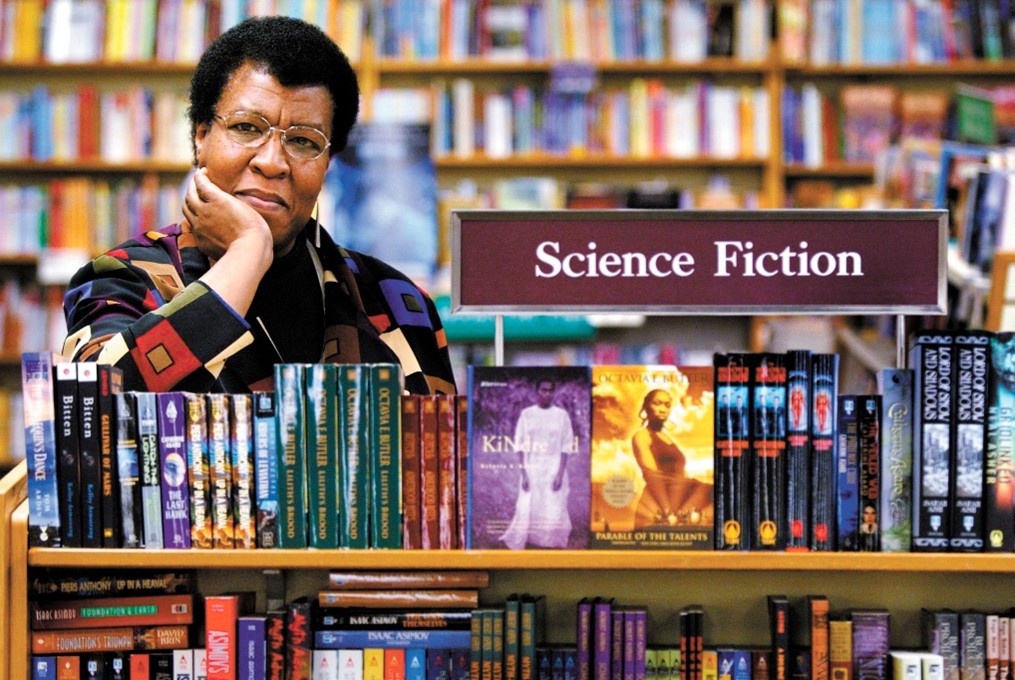

Octavia Butler…Yeah. Horror.

Ladies-in-Waiting

When Americans want to say something is incredulous and inflect sarcasm about something they deem so unbelievable it is all but inconceivable, they say it is science fiction.

What a coincidence.

When we look at a writer like Octavia Butler, we are seeing someone so deftly accomplished that she can weave threads of multiple genres together and let the inferences lie where they may… In other words, she does indeed qualify to be in multiple genres… including Literature. And including Horror.

Yet many Black authors (and I use the designation “Black” to include those who are also not African-American) find themselves relegated to other genres for the alleged sake of Literary Criticism. We seem afraid to just say whether or not we think a work is not-Horror perhaps because of a misunderstood emphasis, or whether it has too many other-genre elements. Instead we seem to grab for Literary terms we do not grasp the full meaning of and hope the general audience of Horror fans does not understand either. So far it has been working. So far we have taken virtually every writer of color and pronounced their writing as too steeped in Literary elements to be considered Horror, as too packed with hidden agendas and racial “coding” for the presumed white majority audience to “get” the meaning of and not feel offended.

Part of the reason we can hide behind Literary Critical terms and use them in ignorance is because of the historical “ghettoization” of the Horror genre in general, which has often failed to attract both serious Literary Critics and writers who want to be taken seriously. We have been left to our own devices with no oversight, both in judging works as genre, and judging them as Literature while fending off a generally poor professional association which all speculative fiction suffers from. Indeed, even many white writers in the past have been known to use pseudonyms when writing Horror so as to “spare” their reputations. But the whole negative “cachet” has distorted our ability to attract serious Criticism and analyze all of our writers fairly – something always magnified by the time it gets to writers of color.

According to Kinitra D. Brooks in her spectacularly insightful book, Searching for Sycorax: Black Women’s Hauntings of Contemporary Horror, “The prejudices against speculative fiction also account for the discounting of fertile research opportunities in the already privileged literary fiction of writers like Toni Morrison and Gloria Naylor. Earlier analysis of their texts focused on the lived realities of their central characters or were given the misnomer of magical realism. Magical realism is a theoretical framework …in which we ‘find the transformation of the common and the everyday into the awesome and the unreal.’ “ (53)

In other words, now that we are on the fringe of seeing Literary Criticism in Horror, we are ironically seeing it first through the Criticism of Literary Writers who write Horror… So a writer like Toni Morrison finds her work Beloved caught in a Critic’s tug-of-war over Horror genre writing-as-Literature and the Black writers’ place in Literature. But this poses a new question: is a person’s writing – any person’s writing – just an unequivocal “statement” about their racial and cultural identity? And if it is, must we always label writing of the minority Other as “protest” Literature instead of genre? What if it is just about making a statement? Because isn’t it almost always interpreted as such when the writer is white?

Besides being unable to adequately define what Horror is and what criteria it requires for a work to be “in-genre,” we find ourselves in that ignorant state mysteriously looking at and judging the writing of all people of color suspecting something more than humor, parody, mockery, condemnation, rebellion, or criticism of the white majority is in play. Yet it might just be about the experience of living while Other… (which may or may not include criticism, condemnation, outrage or exhaustion of a life lived at their own expense). Writing fiction is about writing truth disguised as fiction. It has to stop being about alleged or contrived formula or misguided assumptions and start being about subtext if we are going to seriously pursue Literature in the genre – by writers of ANY color.

Yet especially when a writer is a writer of color and utilizes Literary elements in Horror, we use Literary cudgels on their writing with an amazingly lethal clumsiness. If they are established Literary Writers who write what appears to be a Horror story, we automatically say they are not writing Horror – in effect affixing them to our assumptions about presumed subtext.

This is far easier to do when a Literary writer drops by for a one-off Horror story…In that case we use the rest of their body of work to drag it out of genre and send it packing.

Exactly when did we as a genre decided that a writer must write ONLY in the Horror genre to write Horror? Honestly, we would have to let a lot of writers go – including Poe – if we engaged in such criteria-bending. We would lose almost all of our Literary writers, and subsequently ALL of our claims that Horror IS a Literary genre deserving of Literary recognition and our own claim to a Literary Canon. (If you want to throw Poe, Lovecraft and even Stephen King under that bus, be my guest. But that is the Literary equivalent of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, of cutting off the nose to spite the face.)

If this isn’t racism and bigotry and misogyny, what else is it? Because if we are going to summon the spirits of Literary Theory to exclude such writers from Horror, we darn well better know what we are talking about. When we add “Black” or “Afro” or “African-American” to actual Literary Critical Theory, it is a misuse of terms when that same term is used to justify how a work or a writer becomes not-Horror. Feminism for example, is Feminist Theory no matter what color the feminism. Literary Critics can slip into terms of sub-genre as part of their professional analysis of works. But if one does not have a Ph.D. in Literary Critical Theory, no one else has any business applying or misusing such terms predicated by race as a bludgeon to whitewash a genre.

So why is it being done by anonymous laypeople in Horror? And why is it couched in “fake compliments” as though it is our genre taking the bullet instead of the writer?

Let’s get one thing straight: Literary Theory is that which is used by Literary Critics to examine a work or a catalog of works to weigh the merits of those works to determine their place in the Literary Canon – not to decipher and judge whether or not they are Horror or Mystery or Science Fiction or Westerns, etc. – but whether they meet the High Criteria of Literature. That things are being pretentiously interpreted and applied differently is the fault of the genre leadership(which should be the authoritative, governing body of the genre and which should exercise some discretion of its own; there should be limits and censure, because there should be expertise).

Just how is it that there is this anonymously implied consensus that all writers of color CAN’T be writing Horror? Is this one of the many costs to the genre of not-having the Horror Establishment just sit down and academically parse out the necessary definitions by which all of our writing should live or die – be in-genre or out? I believe so. And I believe the ignorant wielding of Critical Theory and its parts are not only causing more confusion, but costing us writers the like of Toni Morrison and Octavia Butler to merely mention two such capable-yet-ostracized writers of color.

Teasing this out has got to be made simpler. For the sakes of Butler and Morrison and all of the writers of color who need to come after… let’s straighten this out now. Let’s just commit to an understanding.

And let’s start right here.

Because Black women writing Horror is not science fiction… and we have kept them waiting long enough.

The Incomparable Toni Morrison

Magical Realism – Lock or Key to Horror?

One of the most lethal tools in the censor’s toolbox is the overused, but cool-sounding term Magical Realism. This is a Critical term that is used liberally when discussing writing by Black women, and it is always used in such a way that its mere pronunciation is a free ticket out of the Horror genre. Why is the question; because when we misappropriate the term to use in the analysis of white writing, the writer stays a Horror writer. But the term is not meant to address white writing – or Black writing for that matter. We have, in fact, resorted to misusing it to get our own way.

So what IS Magical Realism? According to Encyclopedia Britannica, it is:

(The) chiefly Latin-American narrative strategy that is characterized by the matter-of-fact inclusion of fantastic or mythical elements into seemingly realistic fiction. Although this strategy is known in the literature of many cultures in many ages, the term magic realism is a relatively recent designation, first applied in the 1940s by Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier, who recognized this characteristic in much Latin-American literature. Some scholars have posited that magic realism is a natural outcome of postcolonial writing, which must make sense of at least two separate realities—the reality of the conquerors as well as that of the conquered. https://www.britannica.com/art/magic-realism

This means Magical Realism is all about emphasis and the raw power of subtext. And THAT means also that potentially one sharply delivered element of Magical Realism is expected to “last awhile” in the prose – characteristically Latin prose. A reader is more likely to see the misfortune of a character and then the magical element, so that when asked, a reader is not likely to say something is a ghost story – but rather a story about slavery (for example) with a ghost in it – as in Beloved by Toni Morrison, even when it was conceived of to explain the paranormal with its ghostly presence of history in a work like House of Spirits by Isabel Allende.

The question for the Horror genre is: How much Horror (and what type of Horror) must be in a story for it to be genre Horror? Does the use or misdiagnosis of Magical Realism change things and disqualify a writer or their work?

That answer is “no.” We have only to look at the track record in the genre.

White Magical Realism in Horror?

The Metamorphosis, (oh look – Wuthering Heights), The Graveyard Book, Imagica, Weaveworld, The Stand (Again), Pet Cemetery…

But on the converse, Critical Theorists like Kinitra Brooks propose that the act of labelling a work as “Magical Realism” dilutes the intended Literary messaging. She states: “I am certainly not declaring magical realism an inept theoretical concept – what I am stressing is that the framework does not fully address the racially gendered needs of black women’s creative fiction. It is a theoretical hand-me-down that fits black women’s literature, but not very well – it is in dire need of tailoring to its specific literary themes. I suggest that a racially gendered framework, grounded in horror theory, provides awesome research opportunities to contemporary black feminists.” (53-54)

So here again we have a case of a term being made to “fit” an author or work, and then being used to disqualify it from Horror. We clearly do not yet have enough Theories in place to adequately analyze works that are more than a sum of their theoretical parts (and that is why more Literary Critics — including some of color – are badly needed).

Continues Brooks,“…black feminist theorists have consistently overlooked horror’s almost commonsensical potential to explore the marvelous in our scholarly readings of black women’s fiction. At its most base level Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987) is a ghost story. True, themes of generational trauma, chattel slavery, and mother-daughter relationships are prevalent, but they all occur with the framework of a prototypical ghost story. Charles Saunders muses: ‘the strong supernatural element in Beloved could easily qualify it as fantasy, or, at the very least horror in the mode of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw’…” (54)

Henry James. White guy. Ghost story. Accepted as not just Horror – but canon-worthy Horror.

So even in respecting Brooks’ own opinion that we do not yet have adequate Theory in place to assess the writings of people of color who are addressing historical baggage of more modern characters while and by telling a Horror story (an enduring Literary Critic field problem if you are listening, English majors), I am irritated that we are not embracing these writers as writing Horror… Something that also happens when Folkloric Horror is invoked, because if such folklore is clearly and truthfully derived from an actual living culture, then that writing is automatically consigned to some cultural Literary tradition regardless of the Horror. This has happened to white writers like Charles deLint, Clive Barker, and Neil Gaiman – whose occasional dark fantasy tells culturally relevant stories which has caused them and their work to be unceremoniously “banished” to the Fantasy genre. Imagine what happens when a writer of color dares “go there…” All of this has been our loss.

Misusing the terminology of Magical Realism by painting with some unilaterally broad strokes ALL writers of color, we are also managing to excise the natural connection to Horror that Black writers and writers of color inherently bring to the genre with them. States Brooks, “I suggest that the (even partial) application of magical realism to black women’s supernatural literature is ill-conceived. Morrison herself chafes under the application of magical realism to her novels because the practice is both lazy and ahistorical, because it operates on the assumption that she is not without a literary tradition. Magical realism ignores African Americans’ long-standing oral and literary history of including the supernatural and the fantastical in our narratives…” (100)

And just because it is a cool-sounding term isn’t reason enough to use it everywhere; there is not a one-size fits all version of Magical Realism we could or should strap to all writers of color, or all writing.

I am irritated that we have “given up” Critically by allowing existing Theory and its aspects to be used to perform an inadequate and piecemeal hack-job on LITERATURE…simply because no one has ventured, plotted, and sailed a new course of Theory to address what needs to be addressed. And THEN that we have employed that inadequate Criticism for the purpose of excluding writers from the genre on top if it is maddening.

Here is the example of what I mean, as so perfectly described by Brooks: “The first eight to ten years of literary analysis of Beloved focused on ghosts and hauntings, but only spoke of these supernatural elements in terms of the ‘horrific’ effects of slavery upon the psyche of the formerly enslaved. There were no readings of the ghosts and the possessed as traditional horror and how Morrison employs them specifically within a black feminist dynamic – it remains incredible that so much genre potentiality was bypassed by the very creators of the discipline.” (54)

Read. That. Again.

The Horror genre by its Establishment should be out in front of this right now.

There should be dialogue with the Critical Establishment. We should be working with authors, Literary Critics, academics, and theorists on this exact issue. This is all about the future of the genre – both in readership AND in production.

Are we not addressing this because we are closet racist in our genre’s claim that we welcome Black-and-Other-People-of-Color into our genre? Are we just publishing token minority writers in our Best Of anthologies and paying lip service to make ourselves feel better?

Are we then also novices when it comes to explaining why a writer of color is not Horror, but experts when we make the decision? Because something is going on here. And it doesn’t look honorable.

Literary Critics and Horror genre “experts” have a problem. It is a mutual problem. And we need to stop taking it out on writers. We need to FIX IT.

Weaponizing Literary Theory with Futurism/Afrofuturism and Black Feminism

We have absolutely got to get past the idea that writings by people of color hold no interest for those of us not of color. We have got to realize that we have not lived in a vacuum and that our actions and those of ALL of our ancestors have had consequences. We also have to recognize that He Who Is In Charge of a country and its trajectory, is also to blame for its failings.

White people have been exploring this concept in futurism for a long time now – especially visible in our obsession with apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic stories. Zombies. Pandemics. Robots and machines run amok. Dead earth. Mad Max… White people know that what we have let out of Pandora’s Box is about to end us all.

So why are we afraid of facing our racial past? White people will claim that they don’t want to read stories designed to make us feel guilty about things we personally were not present for. But fine, then. What about things we are standing right in front of today? Do we not know how to walk and chew gum at the same time? How to be proud of our ancestry without using that pride to belittle someone else? Seems not. And that is disappointing, because we all have stories to tell.

We have been playing Critical games with writers of color in the Horror genre for a long time. And when we had a writer like Octavia Butler producing a catalog at the rate she did for so many years right here during this “modern era” of civil rights awakening and equality and such… we have to wonder what was used on her writing to disenfranchise her from the Horror genre.

It turns out, it was the same futurism… relabeled Afrofuturism. Ooooh. Scary. Black people. In the future.

Explains Kinitra Brooks, “Afrofuturism represents a successful articulation at recognizing the fluidity of science fiction, and, to some extent, fantasy as viewed through the lens of race, for it is ‘speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth century technoculture – and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future – might, for want of a better term, be called Afrofuturism…’ ”(68)

So what, you are asking, has science fiction and fantasy to do with Horror?

Gee, I don’t know…Alien, The Terminator, Jurassic Park, Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings ( and then fantastical gremlins, evil fairies, Babadooks… Krampus… ) Because if you think we don’t have white Futurism in Horror, you better toss out all of those apocalyptic Horror anthologies and perhaps The Stand…The Walking Dead…World War Z… Poe’s short story “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion”…

If the only thing we are adding to this winning formula of Horror-and-Science Fiction, or Horror and Fantasy is people of color…once again we have to ask WHY is that a “problem”?

Continues Brooks, “ ‘Afrofuturism’ has become a term for all things black and genre-related (with the exception of horror).” (69)

What – wait – “with the exception of horror” ?!?

“Many authors have been placed under its auspices, most especially Octavia Butler as well as Amiri Baraka, Nalo Hopkinson, Derrick Bell, and even Toni Morrison…” (69)

What – wait — WHO?

Why haven’t we heard these names, oh Horror Establishment? Where ARE THEY when we talk canon?

Once again, the reason we do not know these names is because while the Literary Critical community might be appearing to push them toward the Horror genre, the Horror genre is pushing them toward the Science Fiction and Fantasy genres.

When we decide that Octavia Butler is writing Science Fiction (even with Vampires) then we need to ask why I Am Legend is solidly part of Horror in fiction because of its Vampires (and later movie Zombies) but suddenly becomes Science Fiction when Will Smith is cast as the lead… we are talking a need for some serious soul-searching here.

States Brooks, “Another critic, Mark Sinker, insists that the ‘central fact’ of Afrofuturism ‘is an acknowledgment that [the] Apocalypse [has] already happened – Armageddon [has] been in effect.’ The understanding of the contemporary postapocalyptic existence of Africa and its diaspora centers on colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade – that period of physical, cultural, and psychological loss was the Apocalypse. Afrofuturism…[explores] the very nature of being alien.” (68)

Yet here we are arguing how we cannot identify with this concept even as we embrace the blue-skinned Na’vi of James Cameron’s Avatar…

How blind of us to assume every Black story is automatically about Black angst, minimized to whinery instead of something more powerful and worthy of our attention. How ignorant to dismiss works that use Science Fiction elements as not-Horror when they also have traditional Horror elements.

Octavia Butler. Just sayin’….

Continues Brooks, “Black women genre writers refuse to be what genre fiction expects of them as they consistently fight invisibility and are becoming a notable presence only under their own terms.” (75)

Maybe it is as simple as ultimately not seeing people of color “just” an extra in our genre…about not-being the expendable character that gets eaten first.

And as for Feminism/Black Feminismin Horror? Feminist Theory is one of the most prominently exercised theories in Horror Criticism. Feminism has a long history in the genre – from its Gothic Romance and Ghost Story roots to aliens and dinosaurs… women have long used Horror to vent their protests. Can you SEE the ghosts of future Black Feminism in Jane Austen? In Bronte? In every American ghost story ever written? You should. Because they are there, grabbing ankles from Literary graves.

So why are we so off-put and likely to exclude a work when it gets labelled as Black Feminism?

The minute we insert a racial modifier in front of the word “Feminism” it suddenly spins out of Horror…Yet white femimism in Horror?

The Babadook, Silence of the Lambs, Rose Madder, Delores Claiborne, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Rosemary’s Baby, The Stepford Wives…

I rest my case. And I reiterate: we have work to do in this genre.

Why should we care?

Horror is going to continue to be written – whether the genre claims it or not. We all have tales of awakening to write, tales of identity and struggle, tales that are Literary and sometimes unapologetically pulpy… and most of us want to read each other’s stories…white or Black, Native or Asian…

As for the future of Horror and all of the writers of color who want to be part of this genre, perhaps Bugs Bunny says it best:

Overture, curtain, lights

This is it, we’ll hit the heights

And oh what heights we’ll hit

On with the show this is it…

Let’s get on with it. We’re wasting daylight…

References

Brooks, Kinitra D. Searching for Sycorax: Black Women’s Hauntings of Contemporary Horror. New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, NJ: Rutgers University Press, c2018.

Ferrier-Watson, Sean. The Children’s Ghost Story in America. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, c2017.

Saulsen, Sumiko. 20 Black Women in Horror Writing (List 1) | Sumiko Saulson

Wilson, Natalie. Willful Monstrosity: Gender and Race in 21st Century Horror. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, c2020.

A good deal of this is a reach for me, intellectually, to understand, but it hits home when you talk about specific works in the past v contemporary Afro-labels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately, people who are attaching cherry-picked theory to minority works in order to justify not-calling them Horror are counting on this. While there is academic need for theory in a lot of such writings, it is NOT for the purpose of running them out of Horror — but to better decipher all the subtext (not the same thing). Once again we need leadership in our genre and in Literary Critics to correct the misuse and crack open some interesting new Theories…Otherwise we are hemorrhaging writers and untold works –pulp AND Literary…

LikeLiked by 1 person

KC, Once again, you have written a compelling and deeply needed essay in your second part of this piece. Again, you make extremely important points about horror, literary criticism, and how people are excluded! Bravo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Professor! It is hard to explain why Criticism and knowing more about it is crucial to stopping the exclusion of a lot of writers — including white writers as well as the obviously excluded writers of color. That Criticism is complex to explain and apply is precisely why we shouldn’t be using it to argue WHY a work doesn’t “measure up” to Horror expectation…But is IS necessary to expose the “abuse”…I hope I succeeded on some level 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on charles french words reading and writing and commented:

Here is part 2 in KC Redding-Gonzalez’s excellent essay!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Professor!

LikeLike

A superb essay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I hope the technical dive into Theory made some kind of sense — I know it feels sometimes like reading an insurance policy! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep. Yep!

As I read this, all these very relevant points about how we have failed writers of color in horror, I kept flashing to attending horror film festivals and all the arguments of whether something was/was not horror. Is it suspense? Is it a thriller? Is it a drama? Sometimes, I do believe genre is in perception and ultimately in the eye of the viewer/reader. However, when you identify patterns (like you have in this essay), then you have a more pervasive problem.

And when the “shepherds” exclude works, the “sheep” lose out on so much.

As a writer, I have also struggled with critical theory and all critics apply to a work. Sometimes, the ghost might mean something more. Sometimes, it might just be a ghost story. Every writer, regardless of race or gender, is capable of deciding to write the story either way. If talented enough, they can write it both ways simultaneously. Then once it is inside the reader’s head, they can interpret it a myriad of ways that may/may not have anything to do with how the writer intended it. So to automatically apply a racial lens to every writer of color drastically narrows all those possibilities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Christina, for saying this so well… Our genre is clearly leaderless right now, and I find it interesting that when it comes to “what is Horror” we have a anonymous cadre of experts. But when we all need the particulars and justification, “someone else” did it, “someone else” is in charge. We need LEADERSHIP.

LikeLike

I just bought a used book by Octavia Butler. Not started it yet. You amaze me with your analysis KC – always!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am thinking you won’t be disappointed!

LikeLiked by 1 person