When Horror writers think of Horror as Literature, we think foremost of Lovecraft; Lovecraft is so intimately and unequivocally ours…Unlike Poe, who having been repeatedly devoured by Critics of Olde (who in turn we resolutely believe did not “get” us), seems hopelessly ensnared in academic debate even as he rises as proof that Horror is indeed Literary. Lovecraft is accessible to our imaginations.

Lovecraft is indeed different. Lovecraft is us.

He is the traditionally rejected writer dedicated to his own vision of monsters. He is the rebellious outsider, the flawed character in his own story, a rich man made poor, a lonely man made so by his own inability to navigate society. He is the one who said, “I told you so,” the one who showed up his critics and enemies by outlasting them all, and becoming one of the foremost and most immortal of Horror writers. Lovecraft is our revenge upon all naysayers made real. He is our idol.. because he transcended all predictions and Criticisms of his time. For that, we love and adore him.

But what we tend to forget is how isolated, terror-filled, and haunted his life really was.

We forget he was extolled and emulated only after his death; instead we picture him happy and wealthy, when Lovecraft lived an opposite life of constant poverty and was tormented by his own tailored variety of demons. And those monstrosities were so real he not only wrote about them – he named them and gave them their own worlds as they relentlessly chased him through his. That he might well have been mentally ill is (for most of us) beside the point. Lovecraft represents the struggle of an exceptional writer to get his work perfected and published.

Lovecraft is a community triumph.

And while what Lovecraft wrote is now being identified as the highest form of Literary – replete with a Critic-adored World View, he once was indeed…us. That this may provide a useful hint as to the technique we need to find and put to use is — for many of us — beside the point: it irks us to be reminded of the truth, knowing how passionately we identify with pieces of his life as imagined by ourselves.

And so we do not understand how he performed the trick. Like any good bit of magic, we have missed the essence of the illusion by being distracted by that very illusion.

That Lovecraft might well have performed it by accident disturbs us. We are formula hunters…Pattern seekers. And we want a sure-fire, step-by-step instruction manual.

To get there, we have to recognize the secret of the Secret Sauce; World View is a consequence of personal experience.

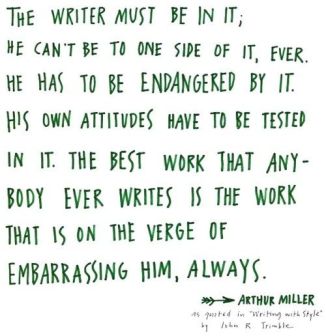

And how you mine personal experience is encapsulated in two sentences of advice we have had drilled into our brains with absolutely no understanding of what was meant:

- Find what scares you.

- Write what you know.

It turns out that writing good Horror depends heavily upon your ability to turn bad memories into good story. It means –even if you are convinced you have neither baggage nor enough life experience – learning to scare the Literature out of yourself… Because if you are going to expose your World View, personal experience is your vocabulary.

Finding What Scares You

In the search for World View, we must look for metaphors. What incidents in your life provide the necessary cover for Life’s Bigger Issues? Chances are, they are the smaller ones…

Yet we are easily overwhelmed by thinking in Literary terms. So it is often better to think in personal ones, and then stitch in the Literary reinforcements at some later point of revision. To do that, we can safely start by using the advice of common How-to tomes…

However, over-used phrases like “write about what scares you” and its near and necessary relative “write what you know” are too nonspecific. They leave a lot open to misinterpretation and we can spend long, lonely years toiling down primrose paths of flat, boring Horror.

But if you are going to write good Horror, you need to understand exactly what is meant by both phrases. There are inextricably linked. And they don’t mean what they sound like they mean: they mean precisely what they mean.

Sound confusing?

Good. That means you are already thinking about it.

When we are told to “find what scares us” in particular, we suddenly become surface dwellers. In essence, we fail to go deep enough into the ugly, emotionally scarred territory of our own subconscious because we spend our lives trying to minimize the damage other people keep trying to do to us and our fragile egos. It is not so easy to reverse course, to dig deep and poke our private humiliations and fears. In fact, it often takes multiple attempts, multiple drafts, and some incredible, hair-tearing moments to pull it off.

According to Charles Baxter in his book, The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot, subtext, or “the unspoken soul matter… that critical twilight zone… that landscape haunted by the unseen” (4) is the provenance of characters. And it is through the artful manipulation of “dramatic placement” that the hidden is revealed – but not just shown. Subtext is a potent revelation that must be deduced, felt, and infallibly honest… where “what is displayed evokes what is not displayed.” (3)

Sounds simple. But this is astoundingly complicated, especially for new writers who tend to grab onto Horror with both hands while minimizing their own world experience. Worse, we are often in love with the creative process. We wallow in the magic like cats in catnip.

For many of us, writing is an escape. It’s like going to the movies and sitting in a dark theater watching a personal showing of an unknown story unfold – this is true in particular if you are an organic writer. To interrupt that process of drafting and probe about for unsettling memories or associations can (in your own mind) wreck the whole thing.

This is largely because being human we choose to insulate our emotional selves from eviscerating wounds. To get it out, we have to trick ourselves. We may have plethora of great and ugly experiences we expect to tap for our writing. But thinking about it is depressing, defeating. It is natural to think of those very personal horrors only in the quiet of your room, when the world is shut out and you feel marginally safe to play with razor sharp images. So we write in circles… in denial.

We create a story with vivid characters and wonderful setting and a plot that seems to lie flat on the page and never quite scares anyone much. We fail to engage our own warp engines…

Yet we all already instinctively know that the best Horror is buried deep: that is where the elevation of the story hides. And our own self-defense mechanisms are constantly plotting against our conscious selves to keep it there.

So when we are asked in public what really scares us – as in a writing class (or when our minds are in public-mode) – we tend to choose and reveal innocuous things that mark us as “one of the group” but not the one who is the most vulnerable. This is not by mistake; not only do we have the savage lessons of predator and prey to remind us of the importance of the safety of numbers, but we have the collective peer pressure of Modern Times…

Continues Baxter, “Our times are marked by mishearing and miscueing and selective listening and selective response – features associated with information glut and self-inflammation” (85) No one really wants to hear our pain, and we are endlessly encouraged to not-think about things we are led to believe we cannot change. It is therefore not so far a leap to burying our own unpleasantries.

This is normal in a world where such vulnerability is met with the most unimaginable cruelties. It means there is a problem with society. And there is your Literary entrance to Horror…

Horror is a unique genre. It is all about the ugly details of how we fail each other, exploit each other, and seek vengeance upon each other.

Yet it is also a very personal genre. Every one of us is a little bit Lovecraft. A little bit King. A little bit Poe. It’s why their writing speaks to us. Why we identify with it, and feel the need to regurgitate our own mortifications.

It is also why it is okay to not be perfect, to have flaws, and to have suffered for them.

Alone in our rooms (even as adults), we often spend way too much time tending our personal terrors, agonizing over things we cannot change, doting anxiously over perceived missteps and mistakes, aghast at our own propensity for victimhood.

The paranoid dialogue is endless, overwhelming, and even debilitating at times. But when the suggestion is made to find what scares us, we think in cartoons; we use place holders like Vampires and scaly monsters in effigy…we ignore the list of darker memories, the unspeakable horrors that haunt our dreams and stalk our hopes and supplant it with lists of petty annoyances like dress codes and politics.

The two lists are indeed quite different, but they are related, and they may be both true. The petty list elicits chuckles or empathetic nods. But it is the first that makes everyone uncomfortable, because we can see ourselves reflected in the mirror like ghosts.

And it is the first list that is most often private. It is the one that circulates in your head and makes ulcers in your stomach. THAT is the one you need to go to…because that one is real. It doesn’t matter if it seems small by comparison to Other People’s troubles. If it haunts you…you are plagued by monsters.

Horror is all about profound truth.

But understand, it is not about confession. You don’t have to write a diary entry to write truth. You do not have to be graphic. You do not have to “out” the child molester in your family. You do not have to have a child molester in your family. But like friend Vampire, you need to draw the essence of the specific fear out to create a solid story around a real Horror.

You have to create resonance. So whether you are writing about a very real personal Horror or imagining one, you have to find the common ground shared by emotions…primal emotions.

Good news: Horror is all about emotions. We all have them. And we all know what is inferred when the right emotional buttons are pushed. You are unique; but what scares you is universal because we all share the same unspoken language of fear. Likewise, how something happened to you is unique. And when you write using those situations or their possibility, no one will ever know for sure if you are being biographical or just insightful and intuitive.

All you have to do if find those unique ways of combining words to summon the images of the monster: that is subtext in its elementary form, the lump of clay all stories start with. You already know how fear makes you feel – that is what is important and potent – everything else can (and probably should be) researched.

It is also where personal experience pushes out character and scene.

This is all Stephen King territory, by the way. King is absolutely tormented by what it is to be an awkward teenager: it clearly made an impression upon him which he cannot forget and which haunts him to this day. It’s why we love him: he gets it. He knows and writes about the awful dread of an acne outbreak right before the prom with your first real crush. He writes about social group rejection. About unrequited love. About how it feels to be bullied. About hating yourself at a time everyone else seems confident and gifted. And then he makes monsters who know exactly how to manipulate those fears.

But what you don’t see is that a whole repertoire of terror is right there in you right now… just waiting to be put to good use. Whether you are twelve or eighty, I guarantee you can dredge up the memories of your most horrible days. Contrary to every piece of adult advice, they do not go away. They live in effigy in your mind forever.

So you might as well put them to work.

Writing What You Know

This little phrase is another snipe hunt novice writers are sent on.

We think we must wait to write then, until we have worked through our first “everything.” But it is not about some vast accumulation of life experiences. It is about empathy. About sentience.

So what if you want to write about a character who commits suicide? You can’t do that and live to tell the tale.

What if a character is an addict? Is the editor suggesting you should indulge before you can write “legitimately” about it?

Let’s be smart about this; of course not. So how do you write what you know?

For one thing, writing what you know means mining your own emotional reactions to personal experience and transferring THAT to your writing.

We all have unpleasantries in our lives, bad memories, embarassments, humiliations, things that went sideways. Nobody’s life is perfect…not really. Of course, maybe the Horror is that everyone thinks your life is perfect…

But in reality, it most certainly is not. Now, if only we as writers can tap into that…to drill down to the bone…

You know how it feels. So you must take how that feels and elevate it. Give those emotions and dreads and horrors to your characters, mask it just enough that there is room for the story itself…. story is biographical but NOT biography.

You can write about a horrible event, a tragic event, a true event – for example… but in order to reach other people at their core, it has to be about the reaction to the event…You must take all of your memories of how The Event marked and marred you, and season your story with those real memories and emotions…leaving just enough off that your reader must imagine the worst that comes after. You want the reader to discover what is happening…remember show-don’t-tell? Well here it is.

But here is the deal. You don’t have to have been there. You have only to be human enough to empathize, to be able to imagine the absolute horror of it.

For example, imagine how it must feel to accidentally kill a child with your car. The emotions are immediate, visceral…unforgiving. Most of us cannot even imagine how one could successfully move beyond that moment of pure hell.

So you don’t have to have actually been there. You can indeed write about anything, as long as you remember that out there –somewhere – someone already has lived it.

You need to care enough to get it right. That means – especially if you are young – you need a reader of your work that does indeed know something about the kind of tale you are trying to tell. Someone who can give you advice and let you know if you captured the reality of it or not. If you do not have the Life Experience required to be accurate in the telling of the tale, find someone who has. It’s not that difficult.

But you also have an obligation to do as much as you can first.

Writing what you know is all about fear. Dread. Social blunders. Awkwardness. Vulnerability…That is something we all already know intimately...because of our very own personal past experience.

You have to dig deep. Mine those emotions and nightmares and reshape them in your characters.

That is writing what you know. Dragging the resonating fears out of us (your readers) is how you write good Horror. You must make your reader uncomfortable. And that means you must make yourself uncomfortable…to scare yourself, as Stephen King says.

And keep in mind that most of our genre’s most successful writers wrote their best as young people – before Life got in its licks, but emotion was king.

Sometimes great Horror is about the raw stuff we fear as young people and utilizing the brevity of youth to just say it…

But how far should you go?

The answer: as far as it takes.

Fear is never a “tah dah!” moment. It is a seedling.

It is a conclusion the reader makes… it is not a salacious moment of abhorrent adjectives. It is not cheap. The coin is very precious and you must spend it wisely. This means that much of the monster is never seen… just a claw here, a fang there, the drag-marks made by the victim.

The secret is you want the reader to imagine the worst and if you succeed in making that happen the worst will materialize right there in your writing… BETWEEN THE LINES. Unspoken. Unwritten…in subtext.

When you are successful, the reader will come away with chills, with a haunted memory of having read your story….not necessarily the details of it, but because you described it like you were there and you dragged the reader there.

Again, Stephen King. It’s why he is so successful at scaring us.

If you are going to write about the most horrifying thing in your life, it may be the best – or the worst – writing you will ever do. But don’t give up. Keep remolding the clay. Have you said too much? Too little? Used the wrong words? The wrong monster?

Did I tell you writing is hard?

Did I tell you writing is work?

Writing is also slow torture.

And Literary Critics look for that torture to last a lifetime of writing. Literary Critics look ultimately at a writer’s catalog of works, rummaging around in World View, looking for subtle changes in the writer and the life’s work the way they looked for World View itself in each individual work. They are looking for a kind of character arc – YOURS.

The “why” comes as part of the sum total job that a Critic does: first they find a Literary work. And then they ask: was it a fluke? Or is the writer Literary?

Because we change as Life has its way with us, it is logical that our World View would change right along with us – either growing deeper and more resolute, or resulting in an epiphany of change. That is what the Critic needs (and hopes) to see over a writer’s lifetime. It is not what you as a writer construct, but what is constructed by the act of your writing.

So what if you are an older writer who is not exactly long on time? Then a Critic needs nuance…perhaps a revelation of those changes that have already happened by presenting good characterization and a passionately true depiction of those earlier views. Yet aging is no excuse: we most certainly do continue to change as we age. And that change will continue to inform your writing…if you remain honest.

Because writing is about the most personal, the most painful, the most outrageous emotions we contain and which subsequently rule and sabotage our subconscious, typically ruining everything that matters. It is all about extracting the pain that you have spent all those years trying to bury, to deny.

Writing is about life and death. Horror is about digging up the bodies.

But more importantly, Horror is all about you – the real you, the alone-in-the-room you.

And no one can tell the story that you will, as long as you write what scares you the most and write what you know. Because to showcase that lusted-after World View, you’re going to have to get personal. You’re going to have to scare the Lit out of yourself.

And nothing scares like honesty.

References

Baxter, Charles. The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, c2007.

Phillips, Carl. The Art of Daring: Risk, Restlessness, Imagination. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, c2014.

Lovecraft’s a most interesting man and writer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed he is…and a whole study in psychology as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

KC, thank you once again for your insightful writing. I hope that you eventually do a book on horror. I would trumpet your writing to the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There goes my head again…it may no longer fit through doorways!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on charles french words reading and writing and commented:

Here is another excellent post on horror from K.C. Redding-Gonzalez

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Professor!

LikeLike

Fantastic writing! Thank you for teaching something very real – truth, resonance, writing from the gut about deeply personal fears and experiences. I am reblogging this too, you deserve the highest praise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, also K.D.! I keep hoping we all can reconcile Literary ambition with our day-to-day writing. It really has nothing to do with arrogance, but a lot to do with wielding craft like a sword!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly, KC and you have that in Spades! KD 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on K. D. Dowdall and commented:

Fantastic writing! Thank you for teaching something very real – truth, resonance, writing from the gut about deeply personal fears and experiences. I am reblogging this too, you deserve the highest praise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again the head….the ego…the doorway!

LikeLike

I’m curious about Lovecraft now. (Never read him.)

However, KC Redding-Gonzalez, and know that this is only a reflection of my Internet Life:

TL;DR.

3,300+ words? Sorry, my internet attention is tapped at 500. And, you are on the internet, yearning to communicate through internet channels to internet recipients of your undoubtedly advanced writing skills. So, no doubt I missed out. But, so did others who, in today’s day and age, we just don’t have the patience to read 10 pages of /whatever/ on a blog post. We don’t. I’m sorry. (But maybe that’s just me (and about a billion other people).)

However, I intent to lookup Lovecraft and take a peek. Thanks for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries. I write long because I’d rather ramble in nonfiction than my fiction. But I also ramble as a point of rebellion.

I like dense material, I like research and critical analysis…what I don’t like is five minute (and incomplete, half-revealed) lessons about writing. So this is my objection to the Internet state of mind that says no one has time or the dedication required to concentrate that long… Perhaps you should worry what the internet-aggravated inability to concentrate and subsequent inattention does to the brain…(Did I mention Horror is also brain science?)

If you love something, you make the time and you give it your attention. You also need to know how to concentrate, focus, and critically think using long spans of attention. I refuse to condense. Readers can stop any time if they choose, but they cannot find writing or research that isn’t THERE.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Brilliant as usual, KC. I promise one day, I’ll write that horror story!

BTW, I love long reads (yours included), and as you put it, “if you love something, you make time…” Thanks once again for this insightful article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Khaya! And might I say I love your poetry…. For anyone looking for a new poet to follow, I recommend Khaya Ronkainen (who embodies the passion to live deep and lead with the soul)! You won’t be sorry….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, KC. I appreciate your encouraging comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person