One of the problems we have AS a genre is the inability or unwillingness to commit to a structure of subgenre.

And while this doesn’t sound like a big deal, it adds up to one because this is part of the foundation of our determining what IS and IS NOT Horror.

And whether HORRROR is HORROR.. or Weird. Or something else..

In order to be both recognized by the Literary Critical field (a goal argued and fought for by generations of writers and fans) AND to be able to properly sort and recognize the vast depth and variety of the genre, we have to commit to some structure. We need to officially claim names for things, define terms, and establish some basic criteria.

Since I can’t find that anywhere, no one is discussing it in the genre or the genre’s Leadership, then I am going to do the arrogant thing and try to start the conversation we are not-having in the genre.

Keep in mind, I am NOT a Literary Critic, I am NOT a professional genre editor, I am NOT a publisher or an academic. I am, however, a lifelong fan, a lay-theorist, and a writer (however good or bad) OF the genre. (So consider me a remnant of that Old 80s’ Horror Boom opinionated conversation group.)

Here is what I think. Now YOU think. And let’s start talking…

Horror’s Missing Hierarchy of Subgenre and Convention

When I was a teenager reading all things Horror, there was constant “genre noise” being made by fans, reviewers, theorists, Literary Critics and editors. Opinions were abundant and substantial; some were armchair authorities, knowledgeable in the history of the genre and its authors; others were passionate supporters of the Classic authors or the Paperback Kings and Queens of popular Horror, pulp fans and Literary defenders. Some were voices from within the industry – editors who made discoveries and choices and quality observations, Critics who were themselves at war over what Literature really is and should be and how it was made. There was always a buzz, debates, arguments and theories to be found in magazines, radio shows, newspapers, and paperback front matter. It was such a constant background hum, it now seems weird to hear absolutely nothing.

Yet here we are.

The closest thing we have to a genre platform is the Horror Writer’s Association. Yet not all are welcome there except to listen to the wisdom of the Chosen Ones. And that is the problem: discussion can only be had when there are differences of opinion and conflicting angles of approach. If the HWA is “it” for debate, we have lost our legitimacy as a genre. We have silenced the majority of voices. And I personally believe there are such voices and fellow-opinionated folk out there, we just have no official forum upon which to vent. And THAT means…

We are not listening to our audience.

So what happened to our genre? Where did all of those voices go, and how do we get them – or their modern equivalent – back in the game?

And what has that got to do with our missing subgenre hierarchy and those oft-alluded to yet never-defined conventions?

Unfortunately a lot. Without words, rules, and definitions, we cannot have discussions. And maybe that has become part of the plan. But I do think that a lot of our silence is a direct result of the upending of our publishing structure, of the delisting of so very many (former) Horror authors, of Someone Somewhere deciding for the greater good of the rest of us what is or should be Horror.

It’s already affecting our already-previously strained relationship with the Literary Critical community. They are asking for our genre definitions and criteria. And if we continue to ignore the questions being posed, it proves not only are we not interested in READING Criticism on our genre, but that we don’t respect either the academic process of Criticism, OR the blood-letting that happened to our writers in arguments on the way to this point. If we REALLY meant we want to be taken as a serious and Literary genre, then we need to start communicating with the Critics who ASK. And we need to be reading their Criticisms to agree or debate their findings. We need to show we care. DO IT FOR POE. DO IT FOR LOVECRAFT… both of whom fought valiantly for Literary recognition of our genre.

But it also affects the writer of Horror. There is already the challenge of self-education of Craft, of the study and interpretation of Literature, and genre history. But when one is ready to sit down and compose a story – not-knowing if one is omitting or over-including some rumor of a convention, not-knowing what subgenre you are writing in or where you can market it – the distraction is absolutely story-stalling. This is my theory of why there is so little adventurous writing in the genre – everyone is afraid of crossing some invisible boundary and being made genre-less. Worse, everyone is afraid of admitting that none of us knows those alluded to conventions.

Yet apparently, neither do our genre “experts.”

Look, we really need to sit down and converse about this – admit where there are holes in our qualitative analysis, admit where we are just speculating on what we propose should be in the genre.

There should absolutely be no shame in not-knowing what no one is taught. So we should feel free to discuss our collective ignorance. And then fix the problem.

Yet there is a persistent and annoyingly loud loop repeating out there that no one is writing legitimate genre Horror or understands what proper Horror is and should be. This message is amplified by the Literary Critic, who is the only one who has the right to say so because it is NOT the job of the Literary Critic to define what is and is NOT Horror.

We are fortunate that this “expert” person (or persons) has no real concentrated power in reality, even if he or she thinks they do and even if they are in any way part of the HWA or traditional publishing and casts a long shadow. The ultimate power in any genre lies in the hands of those who are fans and potential fans of the genre – those who hold the very real purse strings. And since the necessary and Literary Critic-REQUESTED conversation is not being aired by our alleged leadership, then let US the writers and fans of Horror cast the first stone…

Let’s start with the basics. Let’s identify our inconsistencies and our faults. Let’s talk definitions.

Every Organization Needs Rules and Guidelines: Claiming & Naming Genre and Subgenre

If you have ever tried to submit a work for publication, you know the hypocrisy that riddles our genre.

“We want new authors….original work…only the best….must be previously published… like [insert author here]”

Most of us shrug, and press the SUBMIT button. And we typically get the standard Not-For-Us rejection, leaving the process none the wiser as to what was wanted or if we even came close.

The WHOLE GENRE is like this. There is no clear idea of what is wanted in the genre, of what IS genre, or SUBgenre, or “original” or “best”… Just like there is no real Horror canon.

That’s right.

There is NO HORROR CANON.

(Canons are established by Literary Critics. Horror is just beginning the journey of being recognized by the field of Literary Criticism as a Literary Genre (i.e., a subgenre of Literature) and as a result, all we really have is a tiny handful of Critics just beginning to organize and define our genre for the field of Literary Criticism and the purpose of establishing our official canon of authors and works…So…no canon.)

And therefore our first problem is that our genre is constantly referring us to a canon that is not there and does not exist.

But we also find ourselves often being told how inadequate our work in the genre IS. Many of our editors have “bought into” the old and outdated Literary argument that the only thing Literary about our genre is Poe and Lovecraft, or writers like Jackson and Oates. Everyone and everything else is pushed away, even as it is asked for and demanded under threat of failing to remain “in-genre”…

We are constantly criticized for straying out of genre, of being more Fantasy or Science Fiction or Thriller or General Fiction, of writing like we think we are in the 1800’s or flat-out told we clearly violate conventions or need to reinterpret those conventions in order to be “original” (but not TOO original because it still needs to sell).

If you are a writer in the Horror genre, you know exactly what I am talking about; you have probably beat your own head against a wall trying to decipher and decode what the heck everyone wants from you. You may have signed up for classes, workshops, or (God forbid) an expensive MFA degree trying to break down that impenetrable fortress door. And yet you still are not Stephen King. You still work two or three jobs just to keep the roof over your head and your computer updated.

And if you are a reader and a fan, you are probably wondering what the heck happened to our mojo in the genre that ONLY Stephen King seems able to strike our fancy…and keep the genre afloat…

So why is this all such a mystery?

Because we don’t TALK anymore. Because no one “in authority” is willing to assume some responsibility and venture out on a necessary limb to DEFINE the genre – to establish a position that can be refined and corrected and streamlined and debated and refined again until we get it right.

And neither do we make it clear that we need to HAVE A DISCUSSION – to find common ground and agree about the ground rules that the genre needs to abide by.

ALL of these things need to happen and need to happen right now.

After all, literal centuries of our authors (many of them who WILL BE Horror canon authors) who argued the merits of the Horror genre to Literary Critics, demanding the genre be accepted as a Literary genre, did not do all of the heavy lifting for us to stare at our feet and play pocket-pool when the New Literary Critics look at us and ask SIMPLE QUESTIONS that should have been answered a heckuva long time ago.

Where is the organization? The authoritative voice of our “Establishment” proposing their theories about everything the Critics want to (or will want to) know?

The mistake we are making is to fiddle while Rome burns. Critics may darned well shake their heads in amazement and walk away from us…because if WE don’t care, why the heck should THEY? Analysis and Criticism is a detailed, labor-heavy, time-consuming process: whole lives and careers will be given over to reading a LOT of Horror, good and bad. Who wants to bother if we can’t even provide the most basic answers to the questions:

What IS Horror by definition, and is Horror the proper name for the genre?

What are the criteria?

What are the recognized subgenres?

What are the established conventions and examples of works that exhibit those exact conventions?

When and to what extent should conventions be broken and still remain in-genre?

For all of our “experts” in the genre and the HWA, we have NO WRITTEN GUIDELINES OR DEFINITIONS.

None.

Think I’m kidding? Google “Horror conventions”… then find a wall.

It turns out there is no comprehensive list of conventions for Horror fiction. NONE. You can find a sprinkling with relation to the Ghost Story, and with the traditional monsters…But there is no authoritative place to go with an actual list. Only musings. Preferences. Observations. The most you will find is in Film Theory…

So what does this mean? It means no one has a right to toss you, your writing, or others out of the genre. When someone deigns to commit some rules to paper in a place we can all find them, debate them and finalize them…then and only then should anyone vacate the genre.

We are risking everything right now by not allowing and encouraging discussion about where we should be going with this.

This is not to say that there are not scattered, informal discussions out there. There are several Horror podcasts, newsletters, and blogs about. But no one is collecting them, coordinating between them, inviting discussions between groups or participants. Just as no one saw fit to collect all of that valuable front matter of editorials, reviews, and criticisms and theory from past traditionally published collections and anthologies to save for posterity. THIS is our genre history. And it seems to be being relegated to a kind of rite-of-passage-if-you-didn’t-find-it-to-learn-about-it-you-aren’t-a-real-Horror-fan thing.

Besides being a sick, egotistical game, I repeat: this is our history.

And between Technology’s Big Thrill of killing publishing and all of the hard copies that define a history, and an Establishment that clearly thinks it has the sole intelligence and authority to remake Horror in its own image… We stand to lose everything our predecessors have worked so hard for – respectability and recognition.

How do I know this is a real problem?

Almost no one has ever disagreed with me on this blog.

WHY NOT?

This does NOT mean I am always right. It DOES mean we are not engaging with our “base”… we are not connecting… we are not discussing… Because SOMEONE should be saying, “I disagree…” Those of us who have formed opinions and done “a little research” should expect conversation. Yet we find only crickets.

Here are the most urgent of the questions Literary Critics have already ASKED US, and since no one seems to want to say, here are MY answers as a writer, fan, and researcher:

- What IS Horror by definition, and is Horror the proper name for the genre? In my opinion, Horror is the proper name of the genre: the word encompasses everything from that which inspires fear, disgust, revulsion, terror, the supernatural, the paranormal, and the strange or weird. The Weird is only The Weird.

- What are the criteria? I believe either the presence of actual monsters OR the supernatural that are inseparable from the plot is THE criteria.

- What are the recognized subgenres? Well let us explore that question further; allow me to get you started thinking about it…. Because I have been thinking. For years.

I consider there to be eighteen SUBGENRES, and even though there are definite overlaps, I believe there should be just as there are overlaps between genres.

For one thing, writers are not machines; there is a part of writing that remains organic no matter how often we may try to adhere to outlines, and we are wont to weave into our stories many different threads as we construct character and story just as an artist might use all of the colors on his or her palette. Cross-pollination is a natural result. And I don’t see this as a “cataloging” problem; just as we did in library cataloging, what dominates should dictate. Sorting should be an easy matter of deducing emphasis.

For another thing, we need to develop and define subgenre conventions to help stabilize and identify subgenres, and they don’t and should not have to be originality-killing tools of formula, but seedlings of formula. When and to what extent should conventions be allowed to be bent or broken and a work still remain in-subgenre may help clarify the differences between subgenres, and cease to be a tool of overall genre-elimination – something that happened (I believe) because we allowed someone at the top to decide that Horror is one giant genre with one set of conventions. It is not. We are currently torn asunder with subgenres lacking names and definition.

And until we decide on subgenres, we have little use for free-floating conventions, don’t you think?

Here is my list and examples of some of the works and authors I would include in my version of the most prominently noticed subgenres:

The Gothic Subgenre (includes the original Gothic and the Gothic Romance) is traditional and Literary, built on genre precedent. Has formula and strict, already-established conventions clearly applied (such as the isolated manse, the targeted protagonist usually female, dark and gloomy atmosphere, dark family secret); the Horror should be impactful BUT subtle. Examples: Wuthering Heights (Jane Austen), We Have Always Lived in the Castle (Shirly Jackson), Bellefleur (Joyce Carol Oates) The Fall of the House of Usher (Poe) The Old Nurse’s Story (Elizabeth Gaskell)

The Southern Gothic Subgenre (a strictly American regional offering) this is a clear and distinct form of The Gothic that is not fashioned in the strict mode of the European model of The Gothic, but that like The Gothic trends Literary. And while it is also dark, often includes a large “manse” and has a plotline rife with family or town secrets, it also tends to include an undercurrent of dark humor while being set exclusively in the American South, often serving as a coming-of-age story, characteristically drawing on the tragedy of slavery and loss, monsters and voodoo; although according to The Palgrave Handbook of the Southern Gothic, this subgenre is already beginning to expand into other rich areas of the American Southern story with long-overdue love and attention – such as Native American presence in the South, socioeconomic class, and norms of gendered behavior and what has come to be called “the Southern Grotesque”… Feast of All Saints (Anne Rice), A Rose for Emily (William Faulkner), The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires (Grandy Hendrix), The Road (Cormac McCarthy), A Good Man is Hard to Find (Flannery O’Connor)

The New Gothic Subgenre is a mirror of the Old Gothic, but is set historically in more “modern” times – currently this subgenre is starting with World Wars I and II, using much the same formula as Old Gothic and Gothic Romance – same isolated, supernatural-laced settings, the isolated protagonist, The Family Secret, and the ghost. Unlike Southern Gothic, the New Gothic has more in common with Gothic Romance and our English roots than with our cultural failings. However, perhaps it is because the subgenre is just getting started…Things could indeed become much more Literary and interesting; sub subgenre emerging now? Urban Gothic. The Haunting of Maddy Clare (Simone St. James), The Haunting of Cabin Green (April A. Taylor), The House Next Door (Darcy Coates)

The Ghost Story Subgenre is also traditional and typically Literary but includes modern interpretations and pulpy versions of the campfire tale. There are and have been sketchily “discussed” loose conventions, but their remaining in place should not be for the purpose of restricting the story, merely for identifying it as Horror where the ghost CANNOT be eliminated from the plot and where they are a platform to build upon like rhyme scheme in poetry. The Woman in Black (Hill), The Turn of the Screw (Henry James), Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (M.R. James), Green Tea (Sheridan LeFanu), The Ghost in the Rose Bush (Mary Wilkins Freeman), Night Terrors: the Ghost Stories of E.F. Benson (E.F. Benson)

The Weird Subgenre is largely Literary and mostly Lovecraft and Blackwood providing convention blueprints. Because of the higher interest from Literary Critics, it currently already includes a set of presumed “canon-elect”authors (with those who follow in contemporary times being labelled as imitators). It is, essentially, stories that “cannot possibly happen” because they rely on the knowledge of “science of the future” to be understood and “whose terror cannot be ontological in origin” according to S.T. Joshi in his book The Weird Tale. Without new innovation, this subgenre is sometimes thought to be closing or closed, and only the publishing future and Literary Critics can tell. Currently recognized Weird authors are: H.P. Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood, M.R. James, Robert Aickman, Henry Ferris, Clark Ashton Smith, Thomas Ligotti, Clive Barker, Ramsey Campbell.

The Traditional Subgenre is all “traditional” monsters (even future new monsters are added even though what we consider traditional is still rather new as they derive from the first Golden Age of Horror 1930-1950 as led by Hollywood ) – the vampire, the zombie, the werewolf, the witch, the mummy, and Frankenstein variants. Intermittent conventions can be found, and clearly were being discussed at one point within the genre, but there is still no definitive list. (Interview With The Vampire (Anne Rice), Dracula (Bram Stoker), I Am Legend (Matheson), Ghost Story (Peter Straub), The Mummy: a Tale of the Twenty-second Century (Jane Webb Loudon)

Dark Fantasy/Folkloric Subgenre is all based on actual folklore traditions, urban folklore, and fantasy worlds or realities. Regardless of how fantastical or even literal it gets,we should see the folklore roots from here. Urban Fairy Tales are a sub subgenre. Something Wicked This Way Comes (Ray Bradbury), Faerie Tale (Raymond Feist), Rusalka (C.J. Cherryh), Weaveworld (Clive Barker), The Child Thief (Brom) The Changeling (Victor LaValle), The Hidden People (Alison Littlewood), Memory and Dream (Charles DeLint), Book of the Damned (Secret Books of Paradys Book 1) (Tanith Lee)

Dark Science Fiction Subgenre is a blur of science fiction concepts overtaken by dark elements that pose (sometimes by the totality of the story) prominent supernatural or paranormal questions such as the meaning of life, religion, the soul. The Thing (John Campbell) Event Horizon (Steven McDonald), Sphere (Crichton), Bird Box (Josh Malerman), Coma (Robin Cook) Blind Sight (Peter Watts), The Luminous Dead (Caitlin Starling) Nightflyers and Other Stories (George R.R. Martin)

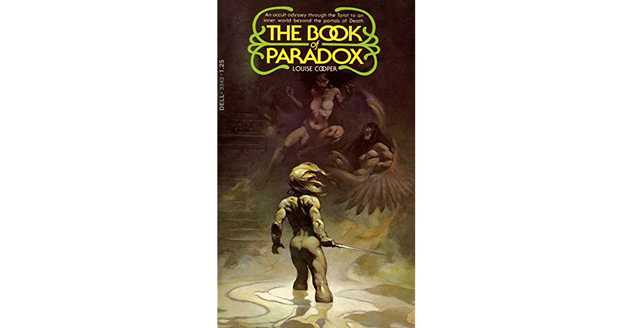

Apocalyptic Horror Subgenre is exactly what it says it is –either about the ending of the world, the surviving of the end of the world, and the loss of world. It does NOT have to be set far in the future, about zombies, vampires or pandemics, but may be about the mystery of how it happens (including right now) or the supernatural instigation or ramifications of such. This would include dead guys discovering they are dead, and trips through purgatory or hell, monsters like Cthulhu coming from outer space, monsters we make through our own incompetent actions and arrogances – but there must be the supernatural and/or monsters embedded in the plot. The Book of Paradox (Louise Cooper), The Devine Comedy (Dante), The Stand (Stephen King)

The Literary Subgenre is void of pulp and commercialism, the polar opposite of the Pulp Subgenre and the endgame of more ambitious Popular Subgenre works; the Horror should be subtle but impactful and can include human Horrors like war, poverty, illness, death, sexual and physical abuse, murder and psychosis, BUT there must be a significant supernatural element. The Birds (and Other Stories) (Daphne DuMaurier), The Winter People (Jennifer McMahon), Mind of Winter (Laura Kasischeke), The Dollmaker (Joyce Carol Oates), Sacrament (Clive Barker), Delores Claiborne (Stephen King), Perfume (Patrick Suskind)

The Pulp Subgenre is nonLiterary, a fictional romp through genre tropes with no explored subtext and light character development, and is prominently featured as comics, graphic novels, and online forums like CreepyPasta (which at novel-length can become Popular). The Sandman (Book of Dreams) Gaiman, Through the Woods (Emily Carroll), Locke & Key (Hill), The Mammoth Book of Kaiju (Sean Wallace)

The Crossover Subgenre is a dump subgenre for writers who write perhaps only ONE piece of Horror or in a style that pushes them to the edge of their HOME Genre, leaving that work literarily homeless but laden with Horror elements that may force also sharing of one or more of our own subgenres. It is also for that block of writing that is simultaneously YA and not quite, Children’s and not quite. We need a place to welcome these orphaned authors and/or works. Piercing Ryu Murakami, I Remember You (Yrsa Sigurdardottir), House of Leaves (Mark Z. Danielewski), Blood Crime (Sebastia Alzamora), Tales of the Unexpected (Roald Dahl), Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone (J.K. Rowling) , Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (Alvin Schwarz), The Ghost in the Cap’n Brown House (Harriet Beecher Stowe)

The Military Horror Subgenre (Just as in the Science Fiction subgenre), this is a place for the wartime survivors, war refugees, military historians, the battle-buff, and the supernatural-infiltrated PTSD writer of battlefield Horror and their jargon-laden stories. It is necessary, and it is a severely underrepresented part of our genre with a huge potential audience and potential field of writers whose stories would not only be therapeutic for their countries of origin, war-torn communities, and survivors, but also an education for those of us so graciously spared the experience of war. An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (Ambrose Bierce), Black Fire (Hernan Rodriguez), Existential (Ryan W. Aslesen), Koko (Peter Straub)

The Period/Historical Horror Subgenre (Just as it is in the Romance Genre) this would be a supernatural romp through a detailed, well-researched historical period. This opens the door to Horror needed by many minorities wanting to explore historical periods, as well as those who want to write the “weird” or haunted western, or who want to write “in the vein of/in the style of older, classic writers” to create a vintage mood. Cry to Heaven (Anne Rice), Phantom (Susan Kay), The Terror (Dan Simmons), The Hunger (Alma Katsu), and all of those Legacy Author anthologies.

The Hauntological Horror Subgenre (which should not be confused with Period/Historical Horror set in a specific historical time, but) is set in “modern day/after the focal event” with the Horror coming from the past OR a future misplaced. This would be the Racial or Species Guilt subgenre where the loss of class, security, environment or self-image is directly related to past events and/or the proximity of the sensed presence of the past. A Stir of Echoes (Richard Matheson) The Wendigo (Algernon Blackwood), Beloved (Toni Morrison), Coyote Songs (Gabino Iglesias), The Tree People (Naomi Stokes), The Only Good Indians (Stephen Graham Jones).

The Holiday Horror Subgenre would be Horror written specifically for and set within a specific Holiday – including Christmas, Halloween and even Valentine’s Day. This would typically be short fiction targeted for holiday contests, holiday anthologies, and holiday periodical features. A Christmas Carol Charles Dickens, Krampus: the Yule Lord (Brom), Something Wicked This Way Comes (Ray Bradbury), Pumpkinhead (Cullen Bunn)

The Humorous/Satirical/Parody Horror Subgenre is horror attempting to bring wicked fun or a satirical twist or parody to the genre. This style needs to be clearly distinct from standard subgenres as Horror fans wanting actual scary Horror do not want silly surprises, and those who want a giggle do not want scary stuff. Legend of Kelly Featherstone (Washington Irving) A Ghost Story (Mark Twain), The Canterville Ghost (Oscar Wilde), Herbert West-Reanimator (H.P. Lovecraft), The Open Window (H.H. Munro/Saki)

The Popular Horror Subgenre is mainstream, fiction-mill Horror, generically produced with actual formula restrictions – including acceptable length and formulaic setting and characters with limited development. This would be the fictional bridge between pulp and Literature commonly known as The Bestseller. Popular can be Literary, but its intention is specifically to sell and perhaps diversify into film. Its aims are all commercial, and should have a formula of conventions that dictate that success (certain events happening by certain pages, faster pace, action verbs, all designed to engage the public on a tale-telling adventure.) Carrie (King), Watchers (Koontz), Rosemary’s Baby (Levin), Hellraiser (Barker), Flowers in the Attic (V.C. Andrews)

I am sure some of my classifications will raise a few hackles here or there, that some of my subgenres will seem to be sub sub-genres to some, that one could argue they seem too overlapping. They also could use more development and specific definition – but then I am just getting started. We have to get something up on the whiteboard, start brainstorming. I say we need to compile just such a list, debate it, vote on it, decide on it. Then we need to get busy establishing accepted conventions for each subgenre – and provide them to any writer or Literary Critic who asks for them.

So there you are: a starting point.

Do you agree? Where do you disagree?

What list would YOU make?

If we are going to grow this genre, mature it into a form worthy of Literary Critical attention, broaden our horizons, increase our creativity, inspire new writers, find new readers, seek out new twists on how we horrify each other, we are going to need appropriate and qualified leadership.

Is anybody out there?